Annual scrutiny survey results: scrutiny and cultural change

We have recently published key statistics and a one-page infographics sharing the results of our annual scrutiny survey. This year seemed to be a much more positive one for scrutiny, which is reflected in a number of important indicators going up and an overall hopeful outlook for the future. However, numerous constraints are still present, and this time around, members and officers raised a number of important cultural issues that prohibit scrutiny from making more of an impact.

Based on survey responses, there are four important determinants that need to be addressed by councils:

- Scrutiny role

- Scrutiny focus/prioritisation

- Organisational culture

- Showing the impact of scrutiny

Scrutiny role

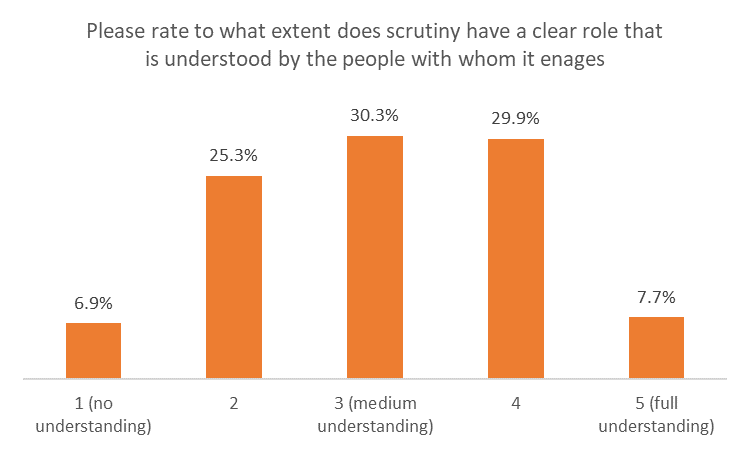

Our survey showed that at least 32% of members and officers believe that scrutiny’s main role and function is poorly understood by the people with whom it engages, which, unfortunately, is up 8% from the previous year.

In ideal circumstances, what should be scrutiny’s role? Theoretically, scrutiny can perform 7 functions:

- Contributing to a wider debate

- Drawing evidence

- Spotlighting issues

- Brokering between actors in government

- Improving the quality of government decision-making through accountability

- Exposing failures

- Generating fear (i.e. the expectation of being scrutinised acts as a deterrence from bad decisions)

In reality, however, scrutiny committees usually have only about 12 meetings per year, and it is impossible to perform all functions equally given such a short amount of time and such a wide breadth of required activities. So, in practice, scrutiny usually does:

- Policy development work (or the overview part of O&S)

- Performance management and post-hoc scrutiny of various sorts (the scrutiny part of O&S)

In order to make scrutiny’s role clear, it might be useful for councillors to reflect on how, specifically, scrutiny can add most value. There will be a niche, or niches, within governance and decision-making at local level that scrutiny can fill – spaces in relation to the oversight of risk and of performance, around the reflection of the citizen voice in policy making, around the operation of partnerships. Deciding on and applying a clear role for scrutiny involves zeroing in on these niches and filling them with productive, outcome-focused activity – something we go on to explain further below.

Scrutiny focus/Agenda prioritisation

The issue of scrutiny’s focus is also closely related to the question of scrutiny’s role. After all, if there is a clear focus, it becomes easier to have conversations with the executive (member and officers), partners and public about what scrutiny exists to do – making it easier to agree the scope, method and outcomes of scrutiny inquiries. There are three common ways of prioritising the agenda and ensuring that a scrutiny committee is sufficiently focused on the task at hand. The first, and perhaps, the simplest one, is to fully align scrutiny’s agenda with the council’s key decisions plan and main priorities (perhaps by carrying out pre-decision scrutiny, looking at decisions a few weeks before they come to Cabinet for consideration). However easy, it may mean that scrutiny probably won’t have enough time to do work outside of Executive priorities and won’t have a huge degree of flexibility.

The second method involves setting up clear criteria for prioritising and selecting scrutiny work. Usually, criteria include:

- Financial ones, i.e. how significant would the financial impact of a decision be

- Community ones, i.e. how many residents or communities will be affected by a decision

- Severity of the decision, i.e. when a decision affects only a small portion of residents, but does so in an extremely profound way

Councils can come up with any number of criteria, but for the purposes of agenda prioritisation, it is vital for these criteria to:

- Be discussed and agreed by scrutiny councillors

- Be clearly spelled out

- Be used when deciding on a work programme consistently

Historically some councils have had quite rigid selection criteria, accompanied by some kind of scoring mechanism, for work programming. This has become less popular in recent years, and we would tend to counsel against it – scoring hides the fact that, at base, work programming is still going to be subjective. By all means use criteria to make judgements, but recognise that they will only ever be a guide.

Finally, scrutiny committees can use a third way of prioritisation, a method that we at CfGS have become increasingly aware of in recent years. We have seen it described as using a “lens”, or “prism”, or “sieve”, to prioritise work; however you choose to describe it, it works as follows. Each scrutiny committee looks at a range of topics with reference to a single area of focus. This focus defines how the topic is looked at. For example, a scrutiny committee can decide that it would focus on social impact; that would mean that its consideration of substantive issues would be carried out through this lens.

When we were discussing potential for such an approach among councillors and officers, we were often met with some resistance. Scrutineers worried that some issues would fall through the cracks, especially given the rather narrow focus of this prioritisation method. Yet, in reality, certain issues already fall through the cracks or don’t get enough attention simply because there is not enough time, resources, and/or support for scrutiny to check each and every major council decision and to make extensive recommendations on each issue. It remains our view that this kind of focus – backed up by a robust and consistent analysis of information by councillors in order to prioritise well – is one of the main ways for scrutiny to be sustainable and relevant in the future.

Finally, whatever your agenda prioritisation method is, and whatever scrutiny’s overall role is, it is important to that is agreed by scrutineers and understood by officers, Executive, and residents alike. In this way, scrutiny both ensures it has a clear role, improves relationship between different parties, and knows where it is heading. Clarity around scrutiny’s role minimises opportunities for uncertainty and misunderstandings.

If you want to know more about scrutiny role and accountability, you can look at our joint publication with APSE available here. If you have any other creative methods of deciding on scrutiny role or choosing scrutiny focus, please email Ed Hammond (ed.hammond@cfgs.org.uk) or give us a call on 020 3866 5100.

In the next blogpost we share our views on organisational culture and scrutiny’s impact.