Governance risk and resilience framework: behaviours associated with the seven characteristics

Behaviours associated with the seven characteristics

The seven characteristics: summary

Principal statutory officers, other senior officers and leading councillors (as well as other councillors and officers) will be able to use this list of behaviours to better understand their own perceptions of governance in the authority.

For some of these, you may not know or see enough to be able to make an accurate judgment; for some, the behaviours you see at your council may not easily match with the examples we have given. That’s OK; all the examples provided are prompts to allow you to structure and organise your thinking. They should specifically not be seen as a checklist, and you should not be adding up the number of “positive” and “negative” behaviours you’ve seen to give yourself a “mark”.

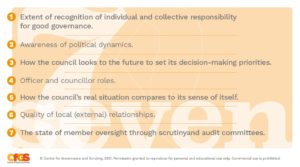

The characteristics invite you to consider the following points:

- Extent of recognition of individual and collective responsibility for good governance. This is about ownership of governance and its associated systems;

- Awareness of political dynamics. This is about the understanding of the unique role that politics plays in local governance and local government. Positive behaviour here recognises the need for the tension and “grit” in the system that local politics brings, and its positive impact on making decision-making more robust;

- How the council looks to the future to set its decision-making priorities. This is about future planning, and insight into what the future might hold for the area, or for the council as an institution and includes the way the council thinks about risk;

- Officer and councillor roles. Particularly at the top level, this is about clear mutual roles in support of robust and effective decision-making and oversight. It also links to communication between key individuals, and circumstances where ownership means that everyone has a clear sense of where accountability and responsibility lie;

- How the council’s real situation compares to its sense of itself. This is about internal candour and reflection; the need to face up to unpleasant realities and to listen to dissenting voices. The idea of a council turning its back on things “not invented here” may be evidence of poor behaviours, but equally a focus on new initiatives and “innovation” as a way to distract attention, and to procrastinate, may also be present;

- Quality of local (external) relationships. This is about the council’s ability to integrate an understanding of partnership working and partnership needs in its governance arrangements, and about a similar integration of an understanding of the local community and its needs. It is about the extent to which power and information is shared and different perspectives brought into the decision-making, and oversight, process;

- The state of member oversight through scrutiny and audit committees. This is about scrutiny by councillors, and supervision and accountability overall.

The seven characteristics: in full

Each of our seven characteristics has a neutral description and is accompanied by a set of associated positive and negative behaviours, which you can find below and should be used as prompts rather than a checklist.

This is about using the “seven characteristics” to keep the health of corporate governance under continual review through reflection on the characteristics and behaviours described. We suggest that all officers and members can look to these characteristics and associated behaviours to understand where they might hold responsibility, or oversight, on an issue where there are risks around resilience in governance.

1. Extent of recognition of individual and collective responsibility for good governance

|

Positive behaviours |

Negative behaviours |

|

Strong relationships between the principal statutory officers and the political leadership, because:

|

|

|

Strong, independently backed whistleblowing systems which employees know how to use if needed

|

A lack of effective whistleblowing systems (which may exist on paper but not in practice)

|

|

Strong audit systems –

|

Weak audit systems –

|

|

Management is not hierarchical – alongside line management arrangements sit clearly understood lines of accountability and ownership which help the council to deal with cross-cutting matters |

Lengthy or complicated management hierarchy which dilutes ownership, responsibility and obfuscates difficult messages from the front line |

|

Straightforward corporate approach to programme and project management, possibly with oversight from a corporate programme board and SMT |

Programme management which obscures clear lines of accountability and elides collective responsibility. |

|

Debriefs from major projects and major decisions are a part of standard operating procedure and are expected to show up weaknesses and shortcomings which need to be collectively owned |

A blame culture, where responsibility for difficult issues frequently shifts between departments and individuals; frequent minor or major departmental reorganisations; top-down mindset |

|

A clear-sighted sense of where shortcomings within the council may cause problems, and trying to bolster capacity and resilience to mitigate the risk of future problems. An approach to learning framed by clear and robust ethical principles, which are articulated and understood. |

Failures excused by external circumstances / matters beyond the council’s control Proposals to learn lessons from failure ignored or implemented in a minimalist way, with a focus on processes rather than culture and behaviours. Ethics are understood only in the abstract. |

2. Awareness of political dynamics

|

Positive behaviours |

Negative behaviours |

|

The role and presence of politics is understood and accepted; it is recognised that councillors are politicians and that their political skills bring unique credibility, legitimacy and perspective to decision-making. Officers while apolitical are aware of political dynamics and manage them sensitively, operating confidently in the political space. Use of the LGA Member Code of Conduct and the “Seven Principles of Public Life” to explore and understood how political dynamics impact on councillor activities, with the Code used as a springboard for discussion. |

Assertions of the need to be “non-political” – an unwillingness to engage in constructive political debate. LGA Code of Conduct and other material integrated into the constitution wholesale without discussion. Ethical principles are minimised or ignored. |

|

Officers act as objectively as possible, being diligent in drawing together a full spectrum of evidence on which councillors can make informed decisions. Officers understood how their own subjectivity and biases influences their work; councillors understand how their beliefs and ideologies influences their own perceptions. |

Debate is discouraged, particularly within the leading political group – there is seen as a single political approach to which all need to be signed up. Officers are treated with suspicion – for example by opposition parties who see them as having been “captured” by the executive. |

3. How the council looks to the future to set its decision-making priorities

|

Positive behaviours |

Negative behaviours |

|

Corporate plan which clearly links long term aspirations with medium and short term activity to meet those aspirations. Plan also clearly prioritises, with a justification for that prioritisation clear to see. Trade-offs inherent in such plans are flagged, understood and acknowledged, especially where they engage with matters which are politically contentious. |

Poor quality corporate plan. This might be a plan which is really just a programme management document, or one whose priorities are set so vaguely that everything is a priority (for example, where everything the council does is somehow engineered to be part of a corporate priority). |

|

Risk awareness and management is part of every decision. |

Risk management that is incomplete or ‘tick box’. |

|

Directors and senior decision-making councillors have the time and space to think clearly and with confidence about the long term – the fact that this thinking is happening is communicated with the wider organisation |

Fixation on project management as a proxy for strategic thinking – directors and senior members spend a lot of time on the industry of programme and project management |

|

Internal and external communication which is frank, candid and mature. Comms which have a consistency derived from the presence of a common understanding of the council and of the area, and the challenges and opportunities that both face. |

Unrealistic optimism, in public statements from the executive and internal communications, which does not align either with internal plans, or with a sound understanding of the wider context. In the context of planning for the future, this could be described as the sense that “something will turn up” |

|

Meaningful thinking and action on what long term pressures and opportunities might mean for the council’s operating model. People throughout the organisation being prepared to innovate to handle these pressures and opportunities, with this preparation being informed realism born of an accurate understanding of the organisation’s capacity and abilities |

A preoccupation with novelty and innovation as a proxy for meaningful conversations about the future and the council’s response to it, including a faddish approach to innovation which is not aligned with the strategic direction of the authority |

|

Sufficient people in the organisation with strategic skills and responsibilities. This may involve a traditional corporate core alongside individuals in different parts of the council who combined functional specialisms with the ability to think strategically; in particular, individuals with political awareness. It is also likely to include succession and business continuity planning for management of senior vacancies, and ensuring the council does not rely on interim appointments for a sustained period. |

A small or non-existent corporate core. This is likely to include few or no policy or research specialists, or specialists in corporate communications, lawyers, financial professionals with corporate responsibility; people who might be expected to protect and support key components of the governance framework. Preparation for the future is seen as divorced from the council as a democratic, political institution. Many senior posts may be filled on an interim basis, possibly in anticipation of a promised organisational restructure. |

4. Officer and councillor roles

|

Positive behaviours |

Negative behaviours |

|

Ethics is front and centre in how officers and members work together. The “Seven Principles of Public Life” are understood, and lived in practice; they act as the bedrock of positive behaviours. |

The authority may have an ethical or values framework but an understanding of it is absent. People rely on rigid adherence to rules and checklists as a substitute for exercising responsible, personal and professional judgement of behaviours. |

|

Councillor, and officer, conduct is taken seriously. People support each other to model good behaviour. This is based on mutual respect despite the presence of robust argument and debate. The importance of political disagreement is understood. |

Conduct is treated performatively; exhortations on “civility” are used to quash dissent and disagreement. Conduct complaints are tit-for-tat and may involve both officers and members. Conduct which is clearly unacceptable is a regular feature of public meetings, with poor behaviour often directed towards officers who are not able to answer back. Resolution of complaints and concerns may be inadequate, with disciplinary systems not working well leading to a sense that certain individuals can act inappropriately with impunity. |

|

Business is carried out through appropriate formal and informal means, in a way that is transparent and understood and which adheres to consistent rules. Not everyone is involved in decision-making, but the way that decisions are made, by whom and at what time is clear, allowing accountability for those decisions to be tracked |

A lot of business transacted in informal meetings between officers and members – for example Director/Cabinet Member meetings, which may not be effectively recorded. This leads to a lack of clarity on exactly who is responsible for making decisions, despite what the scheme of delegation might say. |

|

Senior councillor decision-makers “front up” major strategies and decisions, owning tough judgements and trade-offs. |

A lack of member ownership of big issues. Decisions may pass through member structures, but in a “tick box” way which provides little or no opportunity for influence. |

|

Within a clear and consistent scheme of delegation, senior officers have the freedom to manage operational matters; councillors retain oversight (including through scrutiny) and matters which might be causing concern escalate to members effectively. Predictability in in-year accounting – necessary changes to the in-year budget managed with a clear paper trail and using established principles, overseen by the s151 officer and with the roles and responsibilities of others clearly understood. |

Overt, ongoing member involvement in operational matters in a way that takes up significant officer time, and that may involve member micromanagement. Poor behaviours may be involved; officers may be subject to member bullying. A looseness in the management of budget changes (where senior officers and members are not sighted on emerging issues) or unreasonable exercise of control – neither of which may align with the scheme of delegation. Unexpected non-emergency virements, large underspends and overspends not addressed. |

|

Councillors are kept informed of and engaged in emerging issues – through briefings and discussions between members and officers – and are similarly made aware of major forthcoming decisions. A “no surprises” approach is taken with the members corps on all matters of corporate importance. |

Infrequent or non-existent member briefings on matters of importance. Information is guarded and only shared with a small selection of hand-picked people. |

|

The way that relationships between councillors and officers is mediated is appropriate and relevant to the situation. Senior officers are available to councillors and junior officers work with them to resolve local issues. Councillors liaise and communicate appropriately with officers at all levels. |

Officer and member relationships are over-mediated (through members being expected to push requests and communication through a central mailbox or person) or under-mediated (members making continual, scattergun requests of officers, using up significant amount of senior officer time). Senior officers may be high handed and dismissive towards members’ requests for information. |

|

Councillors lead in setting the organisation’s risk tolerance and risk appetite. Risk is discussed frankly and openly across the organisation. Officers develop plans and strategies which reflect an understanding of risk, its consequences and mitigation. |

No meaningful discussion of risk by either members or officers, or by the two groups together; views of risks and risk appetite are largely personal, and differ significantly between members and officers as the issue isn’t discussed |

|

Personal development is built into day-to-day work, and the appraisal process. Councillors lead and direct their own development objectives; councillor activity (particularly in scrutiny) is designed around this issue. Development includes a focus on “soft” skills – particularly relational skills and political awareness. |

Poor quality or non-existent training and development, including:

|

5. How the council’s real situation compares to its sense of itself

|

Positive behaviours |

Negative behaviours |

|

Council has a clear sense of the experiences of, and outcomes for, local people. |

Official council data providing a skewed and inaccurate picture (perhaps evidenced by significant numbers of member queries or complaints on matters where the council insists performance is good) |

|

Robust performance management system which sits as part of a system by which the council collects and uses information more generally, tied into improvement activity, supportive of the council’s Best Value duties. |

No effective performance management system – dominance of the form and process of scorecards and information monitoring without assurance on data quality or improvement action. The council’s duties to ensure continuous improvement are elided and not taken seriously. |

|

There is a clear sense of who the council’s “nearest neighbours” are on key issues and attempts are made to ensure that this understanding influences how decisions are developed and made. |

A preoccupation with the council’s uniqueness or distinctiveness – either as an institution, or in terms of the area it serves, with that perceived distinctiveness used as a reason to do or not do certain things |

|

Engagement with the wider sector – through institutional membership of a range of sector bodies, networking at senior and junior level, and the use of insight gained in this way (including using good practice / nearest neighbour information intelligently) to influence the way decisions are made. This may also include a positive, proactive and welcoming attitude to external challenge. |

Little serious effort made to look out to the examples of others – little senior attendance at external conferences, little involvement with national institutions like the LGA (no recent corporate peer challenge has been carried out, for example). Attempts are made to uncritically transpose national “best practice” into local operations, or to ignore best practice entirely. Adverse external opinion (from CQC, Ofsted, the LGA or others) is either explained away or subject to unambitious “action plans” which are not effectively prioritised, and which are soon abandoned. |

|

Risk is understood, and an awareness of it is shared throughout the organisation. Risk appetite and tolerance are set, and owned, by councillors. |

No meaningful risk registers at a corporate level, or risk registers which appear to some to downplay risks. Risk registers and associated information tightly managed, and seen only by a select few. |

|

Systems are regularly stress-tested; the principal statutory officers (and councillors) scenario-plan as part of their approach to risk to understand where the greatest risks of failure exist and how these can be mitigated. |

Political and organisational unwillingness to countenance the possibility of failure |

|

Risk mitigation is planned based on existing resources and an understanding of current organisational capacity – risks and mitigation activity are “owned” and monitored carefully, including being escalated where necessary |

Risk mitigation vague, resting on unproven assumptions and relying on magical thinking about how solutions will emerge |

|

Swift action to address problems as they emerge – groups of officers and members work across organisational boundaries to understand problems and tackle them and their impacts. |

Procrastination, strategically and operationally – a sense that “crisis” will bring about innovative solutions by concentrating minds; sweating the organisation’s human assets for minimal return |

|

Continuing to invest in corporate capacity to change and transform – ensuring that the organisation remains flexible enough to be able to take difficult decisions quickly and confidently |

Buying time by reducing capacity to deal with future problems – endless firefighting. Lacking capacity to invest in major change when it is needed leads to a paucity of ambition, or ambition which cannot be met, or a tacit sense of “managed decline”. |

6. Quality of local (external) relationships

|

Positive behaviours |

Negative behaviours |

|

Communication is treated as a strategic function of the authority. The council “thinks out loud”, bringing local people and partners into conversations about the future of the area, and participating in conversations held by others in the places those conversations are happening |

Communicating being mainly operational, and on the council’s terms (both with partners and the public). Public “consultation” is managed by a comms team with little community engagement experience, or alternatively by service-level officers who lack the skill and backing to do it effectively |

|

The information on which decisions are based are published, and added to, publicly. Statutory documents are published promptly and are easy to access. The council invites challenge on its plans – by engaging in dialogue on those plans in a way that feels meaningful and relevant to local people. This often results in a significant change in approach. |

Communication, particularly with the public, feeling performative and mainly about broadcasting the council’s “line” on an issue, with no real interest in changing the council’s approach other than on minor operational points. Members of the public challenging the paucity and poor quality of consultations are dismissed as “difficult” or troublemakers. The council has a poor FOI and complaints record. |

|

The council and its partners work together as equals, developing a common framework of priorities which everyone works to meet. Discussions of risks happens with partners candidly; strong relationships mean that partners support each other. The council does not feel it has to be centre stage. |

Priorities are not aligned with those of partners; partnership discussion is mainly about negotiation around competing objectives. Relationships are performative and superficial, focused on the council thinking what it, as an institution, can get out of partners. |

|

Where possible and necessary, budgets are pooled and/or managed jointly between organisations, backed by strong governance arrangements. The statutory, and other, duties of individual organisations are considered as part of this process. |

Tussles over budgets (with budgets possibly weaponised where the council funds certain partners and their activities, particularly where partners are third sector bodies or there is otherwise a power imbalance) |

|

The council communicates its intentions – short and long term – to its key partners. The political dynamics within which the council operates are well understood by partners. |

Partners (and the council) frequently surprised by unexpected actions of others |

7. The state of member oversight through scrutiny and audit

|

Positive behaviours |

Negative behaviours |

|

Scrutiny uses self-evaluation, and periodic external review, to provide a check on effectiveness, with this feeding into the scrutiny Annual Report Audit Committee is active and engaged and takes an overview of the systems of control, audit and governance |

No regular process by which scrutiny members/officers reflect on the role and impact of the function Audit Committee receives reports but work is tightly focused on financial controls or other aspects of operational management, and does not consider the overall systems of governance or make links between elements of it. |

|

Executive works actively with scrutiny to ensure that councillor oversight is as effective as possible; executive/scrutiny protocol in place which supports meaningful dialogue |

Executive attitude to scrutiny one of exasperation – wanting it to be “good” in the abstract but unable or unwilling to put the proactive measures in place to make this happen (scrutiny’s effectiveness being seen as a matter for scrutiny alone) |

|

Scrutiny prioritises its work driven by a sense of the need to add value and can clearly demonstrate the impact of what it does |

Scrutiny members kept occupied with “busywork” – lots of scrutiny activity without any real sense of its impact |

|

Development needs of scrutiny and audit chairs well-understood – chairs are independent-minded and confident in exercise a leadership role, and command the confidence of their peers |

Weak or poorly-skilled members in chairing positions |

|

Leadership positions in scrutiny shared across parties; all parties have an opportunity to influence scrutiny’s future direction and priorities |

All scrutiny leadership positions (chairs and vice-chairs) held by members of the same party |

|

Culture of scrutiny is challenging and robust, but thoughtful and reflective, focusing on issues of most critical local importance rather than what may be expedient from a party political perspective |

Member disengagement evidenced by overt political behaviours and a hobby-horse approach to work programming (ie members choosing to look at items that interest them rather than those which are of importance to the council and community) |