Governance risk and resilience framework: material for councillors and officers in general

The full governance risk and resilience framework is available on a separate page here. We have also divided additional material into two parts depending on your role within the council.

- Material for councillors and officers in general – those who do not have day-to-day responsibility for leadership on governance issues;

- Material for those with a leadership responsibility on good governance – in the first instance, this will be the principal statutory officers – the Head of Paid Service, the Monitoring Officer and the section 151 officer.

Material for councillors and officers in general

Good governance is everyone’s responsibility.

You are likely to carry out work that intersects with the council’s governance framework every day.

If you are a councillor you need to understand who does what, and where you sit in the decision-making framework.

If you are an officer you will work within legal bounds set by the council’s constitution and the formal decisions made by Cabinet and the Council. You, too, may have direct responsibility for some governance related matters – you may write reports or prepare material to support formal decision-making as a manager or other policy expert; you may support the governance process itself as a democratic services or scrutiny officer; you may communicate with the public and the council’s partners about its decisions as a communications or community engagement professional.

This part of our material explains your role and responsibility and the role and responsibilities of the council’s statutory officers and political leadership.

Your role and responsibility

“[Y]our take on these issues – and particularly on the presence of risks – will be subjective and may not accord with that of others. Part of the process is about refining your own views by reflecting on what others tell you about their own experiences.”

If you are a council officer or a councillor you also have a responsibility for good governance in how you go about your role day to day. This guide is aimed at giving you the tools to reflect on these issues and think about how things might need to improve.

In doing so you will need to consider that your take on these issues – and particularly on the presence of risks – will be subjective and may not accord with that of others. Part of the process is about refining your own views by reflecting on what others tell you about their own experiences.

You may have particular insights, which will mean you have the opportunity to see problems that others haven’t noticed. But you may also think that something is significant and extremely troubling when, in fact, there is a wider context and mitigations in place of which you are not aware. We do not say this to dissuade debate – the opposite in fact. It is only by discussing these matters that councils can, collectively, understand where risks lie and their relative levels of importance.

People in senior roles in the organisation have a duty to ensure that you can do this – that an environment exists in which you can have the confidence to be able to have frank and candid conversations about these kinds of risk, and to work with others to find the solutions. If this culture doesn’t exist – if highlighting these issues is frowned upon or ignored – that is, itself, a marker of concern, and a risk around governance resilience. Under these circumstances, there are still things that you and your peers will be able to do, which we discuss below.

Discussing governance risks if you are a councillor

If you are an elected member your words carry weight. You may believe strongly that the council suffers from significant weakness; you may want to highlight and publicise that view. But you are not a spectator in the governance of the authority – you are part of it, and like everyone else you have a duty to work with others to try and improve things. Your view of the situation may be accurate – but it may not be, and you may need to temper your concerns by comparing your conclusions with those of others. Where you do have urgent concerns – and where you have made efforts to engage with the council’s principal statutory officers to resolve them without success – we have suggestions for other routes you can take that will lead to quick and decisive action.

The role and responsibilities of the council’s statutory officers and political leadership

“Each of the principal statutory officers has specific legal responsibilities. Collectively they have a role to make sure that the council is run in a way that is accountable and transparent.”

There are a few key officers at the top of an organisation with specific responsibilities for a council’s governance. These are sometimes described as the “golden triangle”, although in this material we call them the “principal statutory officers”. They consist of:

- The Head of Paid Service (the Chief Executive);

- The Monitoring Officer (Head of Law, or Chief Legal Officer or similar – this person does not have to be a qualified lawyer);

- The s151 Officer (Head of Finance – this person does have to be a qualified accountant).

Each individual has specific legal responsibilities. Collectively they have a role to make sure that the council is run in a way that is accountable and transparent, that involves councillors, partners and the public, and overall that lives up to the principles of good governance. We have produced separate material which provides advice to these officers on how they can support you to use this framework effectively.

There are others with similar responsibilities. The council’s statutory scrutiny officer has responsibilities around the authority’s member-led overview and scrutiny function. On the councillor side, the Leader of the Council – and Leaders of other political groups – have a responsibility to “set the tone” of how governance, and the council’s political culture, intersect to create a positive working environment.

The framework

The framework provides you, your colleagues and peers with a common language to explore and understand these matters, and helps you to take action to improve.

The framework is about the work that needs to be done to anticipate, manageand adapt to the need for action to address risks in governance. This part of our material provides a basic introduction to the framework – you can find more detailed information here.

Your role as a councillor or officer with is most likely to sit around anticipation – keeping a “watching brief” on matters relating to governance that you are likely to encounter, having the understanding of these matters so that you know what good, and bad, behaviours look like, and being able to bring any concerns to the attention of others.

We think that the council’s principal statutory officers (–the Head of Paid Service, the Monitoring Officer and the section 151 officer) should have a role in supporting you to do the above work. Even if your council doesn’t have formal systems in place to do this, there is still important work you can do to be aware, and take action, on governance matters of which you might be aware.

Stage 1: Anticipating

As we have said, good governance is everyone’s responsibility. One of the main aims of this framework is to provide a “common language” to describe governance risks and behaviours that people can use to share their perceptions of what is going well, and what might be going not so well.

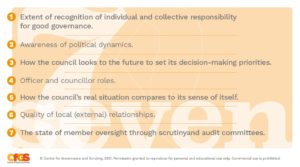

We have produced a set of seven characteristics (below), each of these characteristics has a range of positive and negative behaviours associated with it. You can find these behaviours here; they are arguably the most important part of the framework and reading and reflecting on them is what will help you to make a meaningful judgement on governance risk. You can also find the behaviours listed in a separate document which you can download.

In considering the behaviours the judgement to be made is – to what extent does my experience of things in this council reflect the positive, or negative, examples?

After this section we provide some ideas as to what you can do with these reflections once you’ve set them out. The set of practical behaviours are, we think, the most important part of the framework – they will help you to explore and reflect on your own experiences of governance, and to share those experiences with others.

The characteristics within which the behaviours are organised are:

- Extent of recognition of individual and collective responsibility for good governance. This is about ownership of governance and its associated systems;

- Awareness of political dynamics. This is about the understanding of the unique role that politics plays in local governance and local government. Positive behaviour here recognises the need for the tension and “grit” in the system that local politics brings, and its positive impact on making decision-making more robust;

- How the council looks to the future to set its decision-making priorities. This is about future planning, and insight into what the future might hold for the area, or for the council as an institution and includes the way the council thinks about risk;

- Officer and councillor roles. Particularly at the top level, this is about clear mutual roles in support of robust and effective decision-making and oversight. It also links to communication between key individuals, and circumstances where ownership means that everyone has a clear sense of where accountability and responsibility lie;

- How the council’s real situation compares to its sense of itself. This is about internal candour and reflection; the need to face up to unpleasant realities and to listen to dissenting voices. The idea of a council turning its back on things “not invented here” may be evidence of poor behaviours, but equally a focus on new initiatives and “innovation” as a way to distract attention, and to procrastinate, may also be present;

- Quality of local (external) relationships. This is about the council’s ability to integrate an understanding of partnership working and partnership needs in its governance arrangements, and about a similar integration of an understanding of the local community and its needs. It is about the extent to which power and information is shared and different perspectives brought into the decision-making, and oversight, process;

- The state of member oversight through scrutiny and audit committees. This is about scrutiny by councillors, and supervision and accountability overall.

Talking it through with others

Once you have explored the characteristics and behaviours yourself, you may have some gaps where you’ve been unable to reach a conclusion. We suggest that you share your thoughts with:

- If you are an officer:

- Your team-mates (this might be a project team or a group of people who share the same line manager);

- The direct reports of a particular corporate director;

- Other officers who share your professional specialism (for example, other financial or legal professionals, or other governance professionals);

- If you are a councillor:

- Other members of your Group;

- People who sit on the same committee as you.

Under certain circumstances it might be appropriate to test your conclusions by discussing them with people outside your organisation as well. Membership organisations such as SOLACE, CIPFA, LLG and ADSO may provide mechanisms for this to happen at a national level, and for councillor, LGA political groups (in particular councillor peers) might provide this opportunity, as might the LGA’s principal advisers. At a more local level, partners with whom you may work regularly could have their own insights. More information is available on this kind of help here.

The responses of others within (and outside) your council are likely to be different. Because the framework provides a common language for discussing governance challenges it will enable you and others to think about your subjective responses and how they differ. In doing so, it will give you a more holistic sense of how problems might present themselves and what solutions might look like.

For many matters that you might have identified, the process of discussion may help you to find solutions – or you may need to escalate more complex matters elsewhere in the organisation.

This may be to a corporate director, or to a senior statutory officer such as the Monitoring Officer. We have produced separate material to suggest to such officers the kind of systems that they can put in place to allow you to escalate matters proportionately and effectively.

Stage 2: Managing

The reflections that you make and the conclusions you reach after discussions with others might lead to the conclusion that there are issues with governance at the council that need to be resolved.

Accepting that this is the case will be important – and difficult. For some councils, a defensiveness over where weaknesses might exist may be a symptom of the weaknesses themselves. For some authorities political and organisational circumstances may make admissions of such risk a real challenge. This does not mean that improvement is impossible, but it may increase the need for those from external organisations to be invited to assist to work through the issues.

The framework is designed to operate even where senior management commitment to good governance is lacking. If you work in such a council, there are still steps that can be taken to improve – even if the corporate acceptance of the seriousness of an issue is not present.

Individual officers and members, and members and officers together, need therefore to have the confidence to think through where it is within their power to make improvements, and where the support of others may be necessary. We understand that this may be challenging in some circumstances – external support is available.

- For some, practical improvements could be identified between a small group of officers. This may involve changes to systems, or to behaviours, to address concerns and to strengthen safeguards. It may include ensuring that information and decisions are recorded better, and that roles within, and outside, teams are clear and well understood. These may be improvements that can be made to the way that individual projects are managed, or the management of more general behaviours;

- For more complex problems and/or those affecting the wider council, others need to be involved. This is where more senior officers come in. You should have confidence to bring concerns on governance to the attention of the senior, statutory officers, who should listen to those within the organisation voicing those concerns (as well as providing the space for these conversations to happen). We are providing separate guidance to councils’ principal statutory officers, and the membership organisations supporting those officers, to set out more detail about the role they ought to perform;

- For some complex problems, assistance and assurance from external organisations may be necessary. This may be as simple as making contact with peers or other colleagues to get a sense check on a situation. It may involve professional support from a membership body or political and improvement support from the Local Government Association. These bodies will all be aware of the need to provide support on governance improvement, risk and resilience, and will have their own way of providing this support.

External assistance

“People from outside the organisation may be in a position to provide advice… but ownership should always be taken by those at the local level.”

This may be particularly needed in situations where, as an officer or member raising an issue, you find yourself isolated or part of an organisation which is particularly introspective or defensive, and where you have discussed the issue with others and exhausted all possible local avenues for action. The external help offered from national sector bodies, and/or membership organisations, can help you to navigate these situations. We have provided a list of these organisations and their roles. It’s important to bear in mind that this is not “whistleblowing” exactly. Your council will have a whistleblowing policy, which you should follow for appropriate matters. However concerns about governance risk and resilience are likely not to be adequately caught and dealt with those issues unless there has been actual wrongdoing. Of course if you do suspect explicit wrongdoing then you should follow local whistleblowing systems in the first instance.

When the risk and its potential consequences are recognised and understood, those involved can move to identify solutions.

Putting together solutions for challenges in governance is not as simple as developing an action plans. Solutions are likely to be about focusing on behaviours and organisational culture. The assistance of those in the organisation with a particular expertise and understanding of behavioural issues will be useful. As above, people from outside the organisation may be in a position to provide advice too – but ownership should always be taken by those at the local level.

Engaging in conversations with others is the best way to work out what improvements can be made, and who might take responsibility for them. It will be in everyone’s interests to identify those improvements and a pluralistic, inclusive approach will be important in making sure that everyone with a stake in both the risk, and the solution, is involved.

Stage 3: Adapting

In the medium and long term, it will be important to make sure that improvements to governance “stick” – that they are sustainable, and they are used to support ongoing enhancements to the governance regime overall.

This is about learning and organisational change. These elements of our framework require leadership from the top of the organisation – but individual officers and members hold collective responsibility in making sure that they have practical impact. At an individual level, this is about:

- Staying reflective and self-critical – not making the assumption that solutions, once in place, will permanently improve things;

- Thinking about what improvements to governance in your part of the organisation may mean for others in different spaces;

- Thinking about who you work with, and how those relationships may evolve as governance improvements are embedded.

At an organisational level, some of this learning and development may form part of a change programme, or other activity promoting organisational resilience more generally. It is right that things should be anchored in this way, and commitment from the principal statutory officers will provide this leadership. Our guidance to those in leadership positions on governance goes into more detail on this point.

What to do now?

Our guide sets out a framework for managing challenges to governance, but this is a framework that individual councils must work to flesh out. As a local government officer, or a councillor, you have a responsibility to become aware, and to stay aware, of risks and challenges to governance as they develop in the areas of your responsibility – and to take action to address them when they cause concern.

This has to happen in a way that shares responsibility rather than apportions blame – even where a council’s characteristics mean that it has a blame culture. The way that we have described the challenges and pressures on governance in this guide aims to provide you with a form of language to help you to support your colleagues and your council to break out of unproductive, introspective and defensive attitudes on this. But using it will also require that you model behaviours of mutual support, collective ownership and responsibility. External organisations exist to provide support on this matter and will be there, if internal systems don’t allow these matters to be understood, accepted and acted on.

With this in mind, those organisations authoring and supporting this guide and its contents are keen to provide support in its use, particularly to individual officers and individual councillors who have concerns but are struggling to have them addressed. Part of the challenge of governance is that local circumstances are all different, and there is therefore no clear, national roadmap to improvement and change. You should know however that others in the sector are here to provide support, guidance and advice to resolving problems where they exist in a way which supports local action, local democracy and local decision-making.