Introduction

Questioning is central to the scrutiny process. It is how we challenge assumptions, understand complex systems, hold decision-makers to account, and uncover the stories and meaning behind data. But asking good questions isn’t always as easy. It requires preparation, self-awareness, and the ability to adapt to different people and contexts.

This practice guide is for everyone involved in scrutiny, whether you are a new councillor or officer or have years of experience. It offers a structured way to think about questioning.

You can use this guide to support personal development, shape your committee’s approach to witness engagement, evaluate and potentially improve the effectiveness of scrutiny or as a conversation starter with colleagues about what good scrutiny looks like.

Why questioning matters

In the world of local government scrutiny, questions aren’t just queries; they are the primary tools, the chisels with which we sculpt understanding and drive change. The way we frame our questions profoundly shapes the entire scrutiny process and its outcomes.

What we learn is directly influenced by the depth and focus of our inquiries. A well-crafted question can peel back layers, moving beyond surface-level explanations to uncover the root causes of issues or the full implications of a decision. Conversely, vague or leading questions might only elicit equally vague answers, leaving critical gaps in our understanding.

Who feels heard is another vital dimension impacted by our questioning. When we ask inclusive questions, or when we specifically invite perspectives from diverse stakeholders, including community groups and service users, we empower voices that might otherwise be marginalised. This not only builds trust but also enriches the evidence base for recommendations.

Crucially, questioning is the mechanism through which power is held to account. Scrutiny’s role is to challenge, to probe, and to seek justification for decisions and actions taken on behalf of the public. Robust, evidence-based questioning with a focus on constructive challenge ensures that those in positions of authority are transparent about their reasoning and consequences, fostering a culture of responsibility.

Ultimately, the quality of our questions directly impacts which recommendations are formed. If questions are incisive and insightful, they will support targeted, evidence-based, and actionable recommendations. Flawed questioning, however, can result in recommendations that are misdirected or based on incomplete information.

The dual edge of questioning: opportunities and pitfalls

By asking probing questions, we can bring to light problems or opportunities that might otherwise remain unseen, allowing for proactive intervention or innovative solutions.

In local government, decisions can be multifaceted and involve intricate details. Thoughtful questions help to demystify these complexities, making them understandable to a broader audience and ensuring all implications are considered.

Open and direct questioning, particularly in public forums, inherently promotes transparency. It ensures that decision-making processes are visible and accountable to the community they serve.

By thoroughly examining options, challenges, and potential impacts through skilled questioning, scrutiny committees can significantly contribute to the development of more effective and equitable policies, leading to improved services and better outcomes for residents. In scrutiny this is a key part of forming meaningful recommendations.

However, aggressive or ill-prepared questioning can quickly shut down dialogue, creating a hostile environment that discourages openness and alienates witnesses. When individuals feel attacked rather than genuinely scrutinised, they may become defensive, withhold information, or disengage from the process entirely. Similarly, passive questioning, which might be polite but lacks specificity or depth, may fail to get beneath the surface, leaving critical issues unaddressed and opportunities for improvement missed.

The aim of scrutiny questioning is unequivocally not to “catch people out” or to score political points. Instead, the fundamental purpose is to generate useful insights that lead to action. It’s about building a collective understanding of challenges and opportunities, identifying pathways for improvement, and ensuring that public services are delivered as effectively and efficiently as possible. This is often referred to as scrutiny being a ‘critical friend’.

Creating the right environment for questioning

In scrutiny work, the quality of the answers you receive is shaped not only by the questions you ask, but also by the context in which they are asked. Careful preparation for witness sessions can significantly enhance the effectiveness of scrutiny and foster more open, honest, and constructive dialogue.

When planning for a witness session, consider the following key elements:

- Who is being invited?

Ensure that the individuals invited to the session have the appropriate insight, authority, and experience to speak meaningfully on the topic at hand. Selecting the right witnesses increases the likelihood of receiving informed and relevant answers. There may well be a difference in the approach that scrutiny wants to take depending on whether they are internal officers or councillors or external witnesses, such as members of the public. - Where is the session taking place?

The environment, whether physical or virtual, can influence the tone and openness of the conversation. A setting that feels formal or intimidating may inhibit candour, while a well-managed, neutral, and welcoming space can help put witnesses at ease and encourage fuller engagement.

- What assumptions might the witness bring?

Witnesses may arrive with preconceptions about the nature of scrutiny. They could be nervous, defensive, or anticipating a confrontational exchange. Being aware of this allows you to adjust your approach to create a more constructive atmosphere, where witnesses feel respected and able to contribute honestly. - How is scrutiny perceived?

Witnesses may bring different views of what scrutiny can and cannot do, as well as opinions on its effectiveness. Consider how your tone, body language, and style of questioning might be interpreted. A fair, transparent, and respectful approach reinforces the legitimacy of scrutiny and helps maintain a cooperative dynamic.

By giving thoughtful attention to these contextual factors, you can strengthen your questioning skills and promote more effective scrutiny outcomes.

Steps to put witnesses at ease

Creating the right environment starts well before the session begins. Here are some practical steps to help put people at ease:

- Give advance notice and clear information

Share the purpose of the session, the topics to be covered, and the format well in advance. This helps witnesses prepare and reduces uncertainty. - Offer a pre-meeting or informal conversation

A short conversation before the formal session can help clarify expectations, build rapport, and address any anxieties the witness may have. - Introduce the session clearly and positively

At the start, explain the role of scrutiny, the structure of the session, and the shared aim of improving services or decision-making. - Use open, respectful body language and tone

Whether in person or online, how you speak and behave makes a difference. Avoid aggressive questioning or overly formal language. Active listening, nodding, and acknowledging good points all help build trust. - Encourage clarity and offer reassurance

If a witness seems uncertain or flustered, pause to clarify or rephrase the question. Reassure them that it’s okay to say if they don’t know something or need to follow up later. - Thank witnesses for their time and contribution

At the end of the session, express appreciation for their input and explain next steps. Acknowledging the value of witnesses’ perspective reinforces a positive relationship and supports future cooperation.

Inquiry approaches relevant for questioning

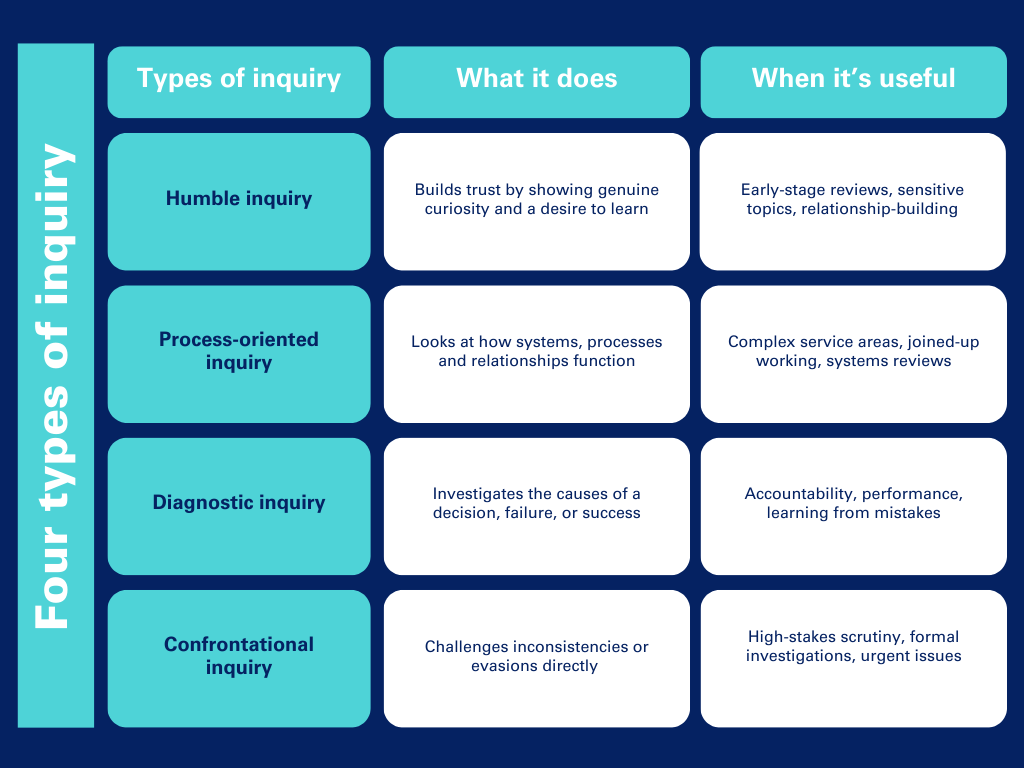

At its heart, questioning is a form of inquiry. It’s a way of exploring ideas, gathering evidence, and making sense of what you hear. It is useful to pay close attention to the approach taken to questioning to ensure that the scrutiny committee is deliberately taking the approach most useful to getting answers and/or supporting the formulation of recommendations. One way in which to do this is to consider the approaches to inquiry that are proposed by organisational psychologist Edgar H. Schein, in his 2013 book: ‘Humble Inquiry: The Gentle Art of Asking Instead of Telling.’ Schein proposes four different types of inquiry. Schein emphasises that these are not rigid categories, and most effective conversations, especially in scrutiny, will involve a blend.

The four types of inquiry are:

A walk through the four types of inquiry

1. Humble Inquiry

Definition: Asking questions in a way that shows genuine interest, respect, and openness, especially when the other person has information you need.

Purpose: To build trust, invite openness, and encourage thoughtful reflection.

Use in scrutiny: We know that Scrutiny’s effectiveness will be reduced if decision makers see it as aggressively critical, which in turn will lead to defensive behaviour and make it difficult for scrutiny to influence change. A way to consciously step beyond this approach is to use humble inquiry. Schein argues that psychological safety, honesty, and collaboration thrive when leaders adopt this mindset. In scrutiny, this approach can be especially powerful when:

- Engaging with frontline staff or service users

- Examining contentious or complex topics

- Starting a review where trust and insight need to be built

In scrutiny, starting with humble inquiry can create the space for diagnostic and even confrontational questions to be more effective and better received later. Ideal for early-stage conversations, developing understanding sensitive topics, and when building rapport with witnesses. Useful when the aim is to learn, not to judge.

Example: “Can you explain how that process supports service users?”

Why it works: It signals respect for the other person’s expertise and creates psychological safety.

2. Process-Oriented Inquiry

Definition: Asking questions to understand the process, events or behaviour. This can be aligned with systems thinking methodologies. The Systems Thinker – Systems Thinking: What, Why, When, Where, and How? – The Systems Thinker

Purpose: To unpick the component parts of a service or decision to examine causation in turn.

Use in scrutiny:

Useful when a conversation feels stuck, tense, or unclear. It helps surface tangible steps that have been taken or are designed to be taken.

Example: “What steps are taken when a service user contact us?’

Why it works: It can move away from blame and bring a useful perspective to service review.

3. Diagnostic Inquiry

Definition: Asking targeted questions to shape or guide the conversation in a particular direction.

Purpose: To explore causes, consequences, or deeper reasoning.

Use in scrutiny:

Useful when trying to unpack complex decisions or understand how and why something happened. Helps committees move from surface-level answers to deeper insight.

Example: “What factors led to that recommendation being made at that time?”

Why it works: It helps probe the rationale behind decisions, especially in performance or accountability reviews.

4. Confrontational Inquiry

Definition: Posing questions that insert your own thinking or assumptions into the conversation. This does not have to be done aggressively, but questioners will be acting from a position of having already made their mind up.

Purpose: To challenge, provoke, or redirect the discussion.

Use in scrutiny:

Best used with care—typically when there is a need to test evidence, expose inconsistencies, or hold people to account. Risky if used too early or too often.

Example: “Didn’t that contradict what you told us earlier about the funding arrangement?”

Why it works: When used strategically, it can surface gaps in evidence or highlight unresolved issues. But overuse is likely to shut down dialogue and may damage relationships.

Designing good questions

Asking good questions is a skill, and like all skills, it can be developed through thoughtful preparation and regular practice. It’s tempting to believe that strong questioning is simply a matter of instinct or natural flair. In reality, the most effective questions are rarely improvised. They are carefully shaped by the context in which they’re asked, the information available beforehand, and the clarity of purpose behind the scrutiny process itself.

Good questioning begins well before a witness sits down in front of the committee. Taking time to review reports, previous decisions, policy documents, and external data sources helps you understand the context. This allows you to spot inconsistencies, identify gaps, and form a working picture of the topic. It also prevents repetition: there’s little value in asking for information that has already been clearly presented. Instead, preparation helps you focus on areas that need illumination or clarification, or exploration.

It is necessary to consider how you will construct this commonality of understanding, being conscious during work programming is a good start. But it is likely that you will need to have a conversation as a committee to reach agreement and develop your questions. A typical approach would be to do this in a pre-meet, but some committees use technology to facilitate the discussion – either at a specified time on teams or similar, or even using WhatsApp.

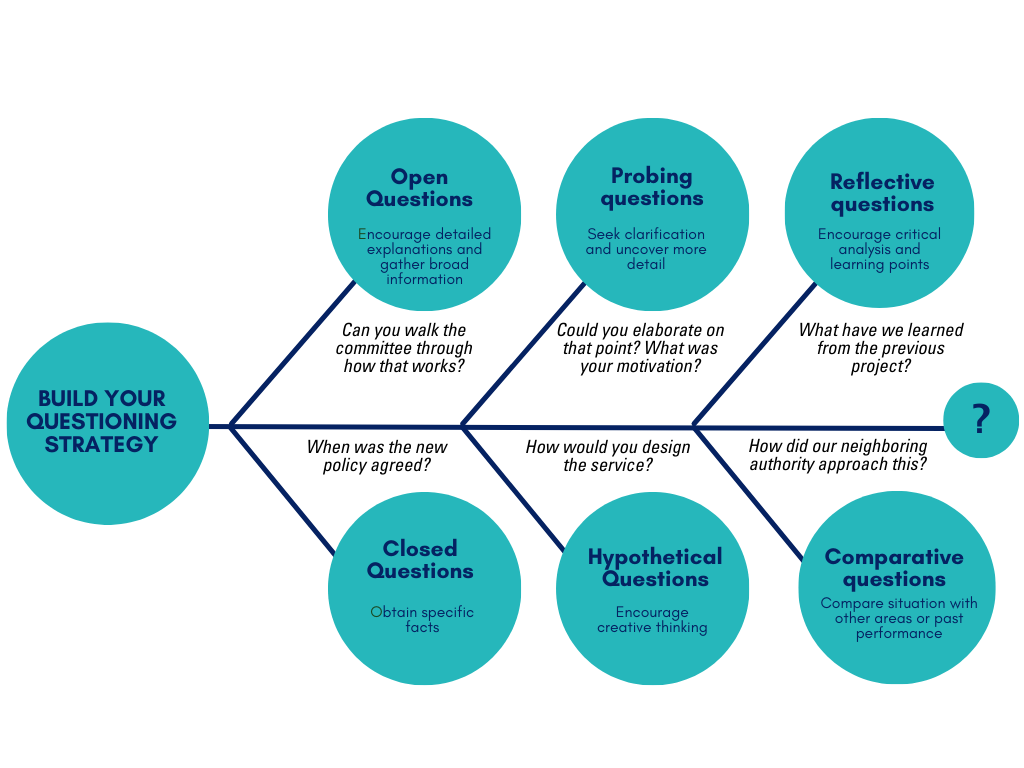

Before crafting your questions, it’s important to be clear about the purpose of the session itself. Is the committee trying to explore the effectiveness of a service? Understand the reasoning behind a recent decision? Assess the implementation of a policy? Without a shared sense of direction, scrutiny risks becoming unfocused or reactive. Clarity of purpose ensures that questions serve a coherent line of enquiry. It also helps to identify what types of questions will be most useful. Being clear about what the committee needs to learn will help shape the tone, content, and structure of the questioning.

The diagram above illustrates a range of question types that can be used to develop a robust and purposeful questioning strategy in scrutiny work. Each type of question serves a different function and can help elicit different kinds of information, insight, or reflection. By consciously selecting the type of question that best suits the moment, scrutiny members can better explore complex issues, challenge assumptions, and support learning and improvement. Start broad, then funnel in. Think about layering your questions to explore multiple angles.

Even with the best preparation, effective questioning also requires flexibility. Witnesses may respond in unexpected ways, offer new insights, or challenge assumptions. Skilled scrutineers remain alert to these shifts and are willing to adapt their questions in the moment. This means resisting the urge to stick rigidly to a pre-written script. Prepared questions are essential, but they should act as a framework, not a straitjacket. The best questioning happens when members can move fluidly between prepared lines and spontaneous follow-up, using curiosity and insight to deepen the discussion.

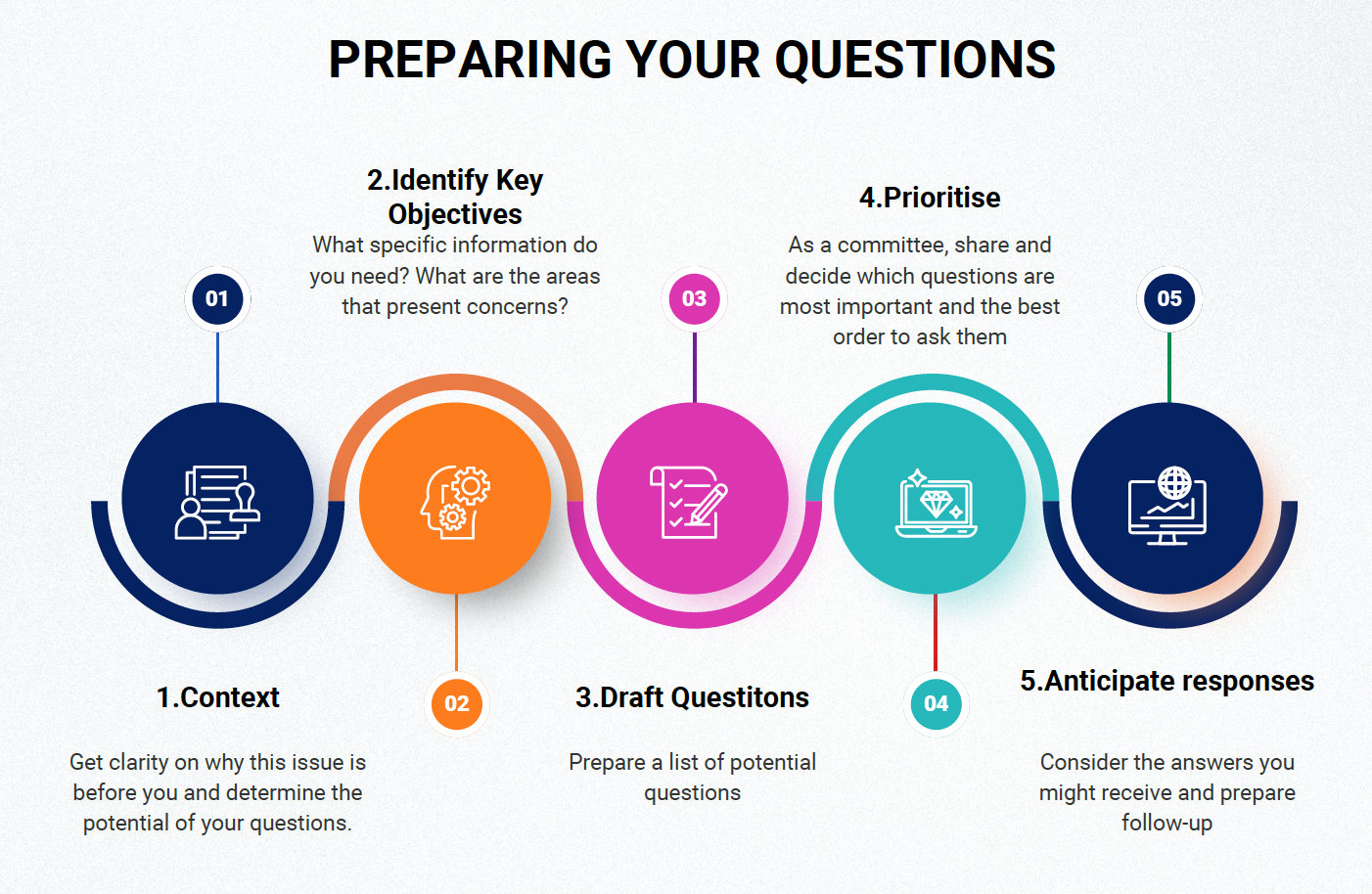

This infographic sets out five key steps for preparing effective scrutiny questions. By clarifying the context, identifying objectives, drafting and prioritising questions, and anticipating responses, committees can approach witness sessions with focus and confidence. Working through these stages together helps teams ask sharper, more purposeful questions that lead to better scrutiny outcomes.

Asking your questions

Effective scrutiny is rarely the result of one person’s questioning alone. A strong questioning strategy is most effective when it’s developed and delivered by a high-performing team. In scrutiny, this means members and officers collaborating closely, before, during, and after witness sessions to plan, refine, and coordinate their approach. High-performing teams are clear on their shared objectives, communicate openly, and make the most of each member’s strengths. By agreeing roles, for example who will open up lines of enquiry, who will follow up with probing or comparative questions, and who will reflect on learning, teams can avoid duplication, ensure coverage of key issues, and maintain a purposeful flow. This teamwork not only improves the quality and coherence of questioning, but also creates a more professional and constructive environment for witnesses, helping scrutiny have greater impact.

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

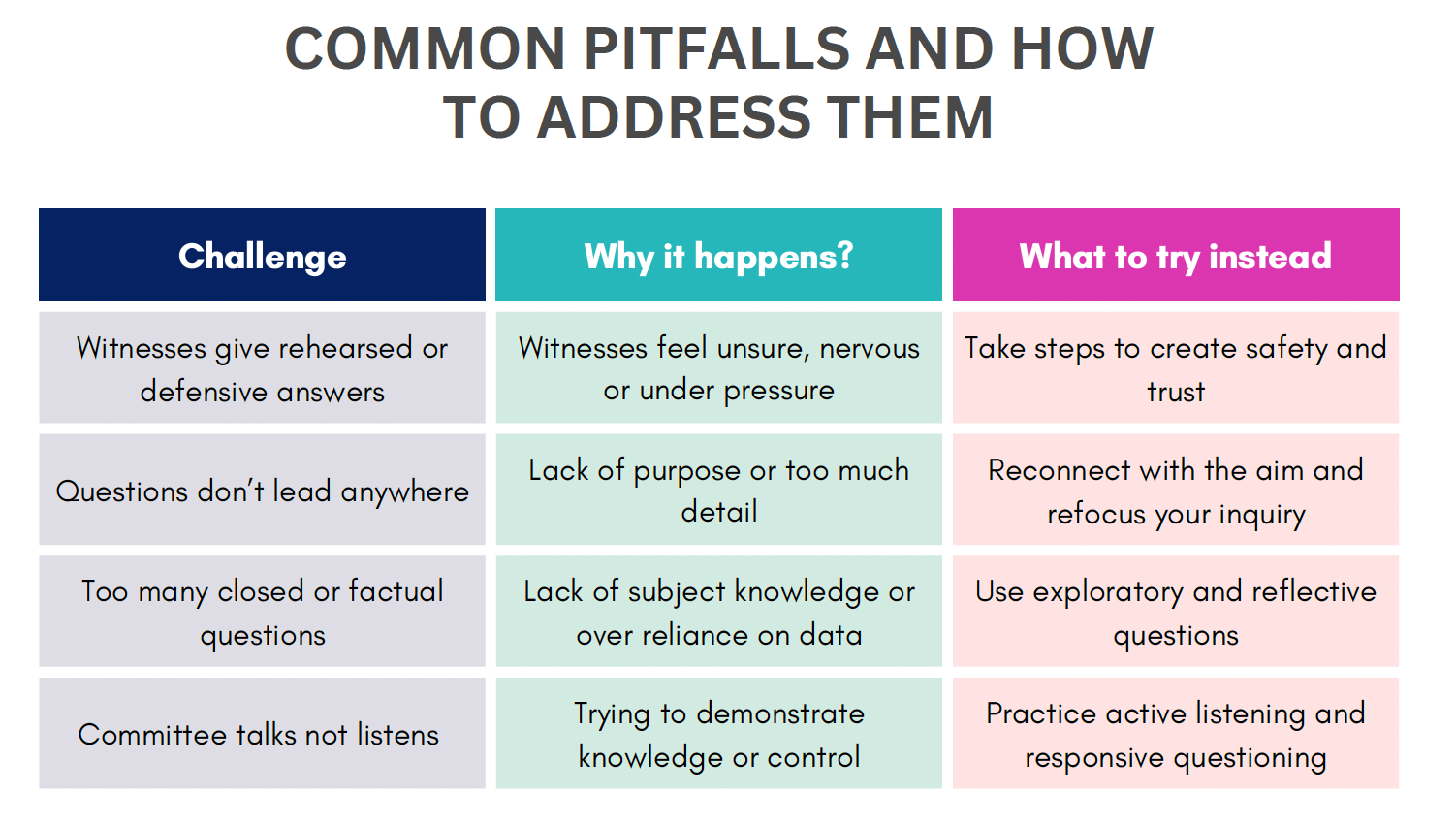

This table is designed to help scrutiny members reflect on the challenges that often arise in questioning, and to provide practical ideas for avoiding them. In many committees, the same difficulties occur; witnesses sometimes feel defensive, questions drift without purpose, or members rely too heavily on factual enquiries. These issues can reduce the effectiveness of scrutiny and prevent the committee from getting the insight it needs.

The infographic aims to prompt deeper thinking about why these scenarios might happen and how to shift practice in a more productive direction. These reminders help committees to step back and consider not only the wording of their questions, but also the atmosphere they create and the behaviours they model.

Tips for avoiding pitfalls

When witnesses feel defensive or rehearsed, it is often because they feel under pressure or uncertain about the intentions behind scrutiny. The solution is to create a safe and respectful environment. This can be done through clear introductions, setting a constructive tone, and acknowledging the value of witnesses’ contributions so that they feel able to share openly.

Questions sometimes drift without purpose or become bogged down in detail. To avoid this, committees should regularly step back and remind themselves of the central aim of the inquiry. By keeping the bigger picture in mind, questioning stays focused, purposeful, and more likely to generate useful answers. The chair of the committee has a clear role here as well.

Relying too heavily on factual or closed questions limits scrutiny to surface-level detail. These types of questions can be useful for clarification but rarely achieve deeper insight. By shifting to more exploratory or reflective questions, committees can encourage analysis, evaluation, and discussion of lessons learned. This point speaks to the culture of scrutiny and how reports are presented.

One of the most powerful ways to improve scrutiny is by genuinely listening to witnesses. Too often, committees focus on what they want to say rather than responding to what has been said. Active listening combined with follow-up questions that build on answers makes scrutiny more responsive, and revealing.

Consider who’s in the room and think about experience, roles, and perspectives before you frame questions. There’s a range of learning styles to be aware of before you jump in.

All resources

All resources