Index

All councils will be planning for reorganisation in different ways – and will be describing the stages of the process differently. The five steps that we are laying out in this guide may not map perfectly to the stages that that staff in your authority will have identified – but we think they are useful in understanding the different, evolving requirements placed on scrutiny functions during this period.

The LGA has prepared a devolution and local government reorganisation hub, which contains a wide range of regularly-updated material about Local Government Reorganisation (LGR)

In this guide

- What LGR is

- What it involves

- Roadmap for LGR

- Why it is happening

- Learning from others

- Principles underpinning scrutiny’s role and involvement

- Scrutiny’s role at each of the five steps towards LGR

- 1. Finalising proposals and waiting for Government’s decision

- 2. The structural change order

- 3. Joint committees and establishing the shadow

- 4. Scrutiny during the shadow year: in the sovereign councils and in the shadow

- 5. Vesting and what happens after

What LGR is

A brief explainer

Local government reorganisation (LGR) is a process that sees a large number of councils, often in a two-tier area (where there is a county council working alongside a number of district or borough councils), being restructured to create fewer, larger unitary authorities.

What it involves

In brief, reorganisation involves:

- Developing proposals for how many new councils there should be, what their boundaries should be, and how many councillors they should have. Councils in an area will submit (sometimes competing) proposals for change and Government will take a decision on which proposal it wishes to take forward based on criteria set out in Government guidance.

- Statutory consultation. The legislation requires consultation both with any council that has not submitted proposal, as well as “any other persons considered appropriate” (as the guidance puts it).

- Government decision to implement a proposal. Decisions will be made based on the criteria that Government has set, having regard to representations and responses to its statutory consultation. In the current cycle of LGR, this part of the process will have concluded, and Government will have taken a decision, by the end of 2025 or start of 2026 (in Surrey, on an “accelerated” pathway, this will happen sooner);

- Once Government has made its decisions on new authority areas, establishing informal joint arrangements for the new council areas. At this stage, these forums or working groups of leaders will usually appoint programme leads from amongst the sovereign councils’ officer cohorts to take forward thinking on a range of workstreams. This is likely to happen from November onwards, although in those areas where agreement between councils may already have been reached, arrangements may be more advanced. Where councils disagree with Government’s decision, forming these informal arrangements may be difficult;

- Establishing formal joint arrangements further to a “structural changes order” laid in Parliament by Government. The Order will set out the name(s) of the new authority/authorities, their boundaries and the number of councillors they will have, as well as confirmation of the date of the first election for those authorities (in May 2026). This is an administrative process and not subject to debate – the Order is laid, and comes into force, on the same day. The laying of the Order – which will probably happen in most cases in January 2026 – involves a requirement for the authorities concerned to establish formal joint committees. This is likely to happen in January or February;

- Setting up the new council or councils in “shadow” form. For around a year the new council or councils will operate alongside the old councils (usually described as the “sovereign councils”). It won’t have any direct responsibility to provide services but it will need to prepare to take those services over – this involves employing senior officers and agreeing on important policies, as well as setting a budget. The shadow election will take place in May 2026 and the shadow authority/authorities will come into being on this date, replacing the formal joint committees. At this stage although the shadow authority will legally exist it will have no staff and a budget only sufficient to organise its core logistical activities – including the appointment of senior staff later in the year. For the time being, work to develop policies (and an operating budget) for the new authorities will be taken forward by workstream leads from existing sovereign councils;

- Planning the transition of services from the old councils into the new councils. The focus of transition is about ensuring that service provision continues to be “safe and legal” – that the transfer of responsibility is seamless. This involves the formulation and agreement by members of the new council arrangements for “day 1”, and the agreement of the first proper budget for the new council in February 2026;

- The final legal transfer of services on “vesting day”. The day when the new councils “vest” – when they start being the new, permanent sovereign councils for the area, is the day after the old councils for the area are abolished;

- The ongoing “aggregation” and “disaggregation” of services. Because in a two tier area different services are delivered at different levels, those services need to be redesigned to map onto a new geography. Design work for this will begin when the councils are in shadow form but it cannot begin to happen until after the new councils vest. The process of aggregation and disaggregation will continue for some years after vesting day, as local difference in the organisation, staffing and delivery of services are gradually altered to introduce consistency across new council areas.

Government has produced a summary of the LGR process which explains some of these arrangements in more detail: Summary of the local government reorganisation process

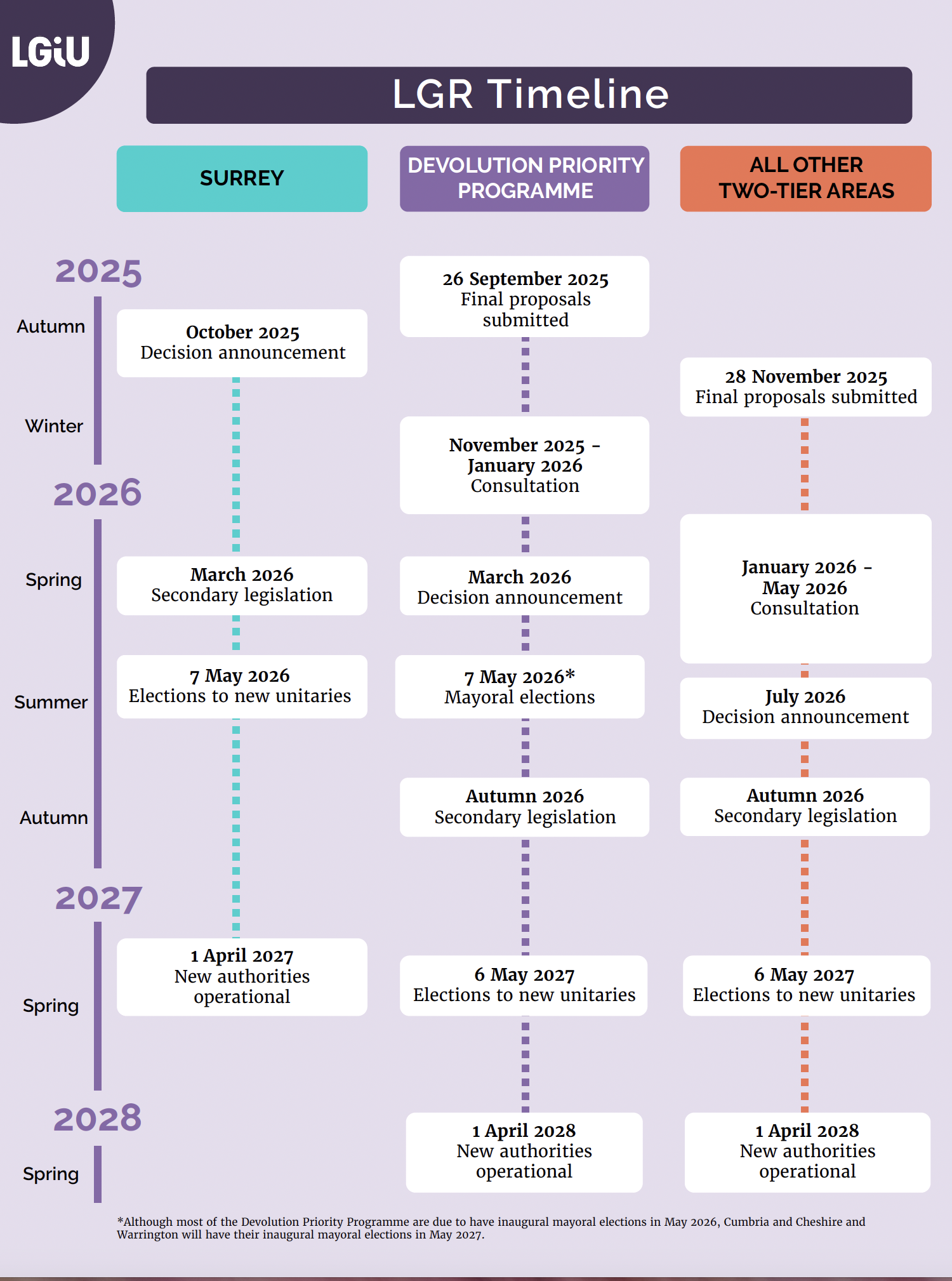

See this journey on a timeline below:

This is a complex process. To aid thinking – and to support action on scrutiny’s role throughout – we have organised it into five steps, which we cover in detail in the next section.

Why it is happening

Government has decided that it wants to see a full unitarisation of local government in England by the end of this Parliament (2029). The process seems sudden – but it is the culmination of a trend that started in the 1980s and has continued, in fits and starts, ever since.

Government’s drivers for LGR are:

- Efficiency and the need to find financial savings. Reorganisation – on its own – will not result in substantial financial savings. Councils are likely to realise greater benefits from the redesign of services that accompanies LGR (ie the merging and dividing of services to meet new geographic boundaries) Major savings (and major service transformations) do take more time to realise.

- Public service reform. A simplification of the “local government map” is seen as a way to create larger authorities better able to engage with decision-making across a wider area as constituent councils of “strategic authorities” – authorities which already exist in many areas. Even so, LGR will still require that new councils work with public and other institutions whose boundaries will still be different (the NHS, for example)

You can find more information about Government’s approach, and the wider agenda on devolution and public service reform here:

Local government reorganisation: Policy and programme updates

Learning from others

What have others done?

There are lots of lessons that can be learned by the approaches taken in areas which previously underwent LGR. Every area is different, with different needs and drivers. But looking through committee papers, and reading publications which seek to draw together these prior experiences, is likely to be useful. The dates in brackets are the vesting years of the new authorities.

Dorset (2019) – A county with six districts, and two unitary councils (Bournemouth and Poole) was reorganised into two new unitary, Dorset and BCP;

Buckinghamshire (2020) – A county with five districts was reorganised into a single new unitary, Buckinghamshire Council.

Northamptonshire (2021) – A county with seven districts was reorganised into two new unitaries, West Northamptonshire and North Northamptonshire.

Cumbria (2023) – A county with five districts was reorganised into two new unitaries: Westmoreland and Furness, and Cumberland.

North Yorkshire (2023) – A county with seven districts. On reorganisation, the districts were abolished and the county council became a unitary authority (see below).

Somerset (2023) – A county with five districts. On reorganisation, the districts were abolished and the county council became a unitary authority (see below).

Other reorganisations happened longer ago in time, when the policy context was different – but may still be useful to look at to understand some of the long-term impacts arising from the exercise.

What lessons can be learned?

Overall lessons from these exercises – from a governance perspective – are that:

- Early dialogue is important – within councils and between them;

- The capacity requirements of reorganisation are significant, and agreeing which individuals lead the practical work can be difficult. Managing the capacity constraints – and accountabilities – around LGR is one of the most difficult things;

- Every process looks and feels very different. While there are broad lessons from people’s experiences overall that can be used to inform what people are doing now, a lot of the detail will be specific to time and place;

- “Safe and legal” transition requires research. There will be a significant amount of local “wrinkles” – idiosyncrasies in local governance and delivery arrangements – that will need to be managed. This means that individual councils’ governance arrangements (including the constitution) must be ready to withstand the stresses of a process that will require real clarity from everyone about duties, rights and responsibilities.

It is worth noting that in the vast majority of cases, reorganisation means the abolition of all of the councils in an area, and their replacement with one or more wholly new authorities. However, in two recent instances – North Yorkshire and Somerset – the LGR process involved the districts in those areas being abolished, while the county council took on district services and was recategorised as a unitary authority (changing its name in doing so). We don’t yet know whether Government proposes to follow this model for the establishment of future whole-county unitaries.

CfGS plans to publish further material which draws together insight from previous LGR areas later in 2025.

Principles underpinning scrutiny’s role and involvement

The success of LGR hinges on good governance. Good governance through the LGR process itself hinges on strong assurance – the presence of systems to ensure that the complex projects and programmes of work associated with LGR are being managed. Scrutiny is an important part of this assurance activity.

Reorganisation is a complex process, which intersects with the “business as usual” activity undertaken by sovereign authorities – that is, ongoing service delivery. It imposes significant resource capacity challenges both during the process, and afterwards for the redesign of those services in new authorities.

The breadth and nature of this challenge means that scrutiny’s approach needs to be purposeful. What we mean by this is that it needs to be framed in such a way that maximises the impact that it will have on the process, and the outcomes of the process, for local people.

What scrutiny can look at

Government’s statutory guidance on overview and scrutiny in local government (revised and updated in 2024) highlights the need for scrutiny to be able to clearly articulate a role. This is particularly the case for LGR, where the breadth and scale of the topic involved – which encompasses all parts of a council’s operation – brings risks around scope creep and the potential that scrutiny will duplicate activity happening elsewhere in the council.

Scrutiny can support areas to:

- Ensure that a wider group of members than just the leadership are sighted on, and meaningfully oversee, the complex range of activity associated with LGR. Scrutiny provides transparency through the process – a way of ensuring that members are sighted on what is otherwise an opaque process managed by Cabinet members and senior officers.

- Manage what might otherwise be choppy and difficult relationships – particularly where there is not necessarily agreement across the place about the post-LGR structural model. Scrutiny – especially joint approaches to scrutiny between sovereign authorities and the shadow – has the potential to build positive relationships, but managed poorly it will end up providing another outlet for disagreement;

- Assist in the management of some of the complex risks associated with LGR – immediate risks relating to the “safe and legal” transition of services into new authorities, and longer-term risks around the aggregation and disaggregation of services;

- Consider capacity pressures by reviewing the impact of “business as usual” activity on the LGR process. Councils must continue to deliver their services right up until vesting day. For these sovereign authorities the pressure of doing this alongside planning for the establishment of new councils brings with it capacity challenges that scrutiny can seek to understand and manage.

- Support new authorities to develop a deep understanding of the area they will be serving by using scrutiny to provide insights on the needs of local people. LGR will see significant turnover of both officers and members. A lot of accumulated knowledge and insight into the local area is likely to be lost. “Sovereign” scrutiny can support the new councils by carrying out task and finish work that will provide insight into local people and their needs that will bolster existing data and other information.

In this guide we lay out five steps towards LGR, and these different tasks are likely not to all hit at the same time. Part of the process of agreeing a role for scrutiny will include determining what scrutiny might do at each stage.

Agreeing scrutiny’s role

Part of the process of clarifying scrutiny’s role – what it will do throughout the process – is agreeing that role both amongst scrutiny members, and with others.

Some councils already have executive-scrutiny protocols. These are agreements that set out mutual expectations and understandings between scrutiny members and the executive – we explain how these might be developed, and how they might operate, in practice guide Relationships for Effective Governance and Scrutiny

It may be helpful for members to revisit these protocols where they exist, incorporating in them more specific arrangements to ensure that LGR scrutiny runs well alongside wider systems for ensuring balance, clarity and focus in what is likely to be a complex and demanding work programme. This may include revised expectations around the sharing of information and the way in which scrutiny can expect to feed into both the LGR process as well as its ongoing “business as usual” work. If no protocol exists a separate memorandum of understanding briefly setting out scrutiny’s expected role in respect of LGR, and its core ways of working, will be a way of clearly setting out mutual expectations. Ensuring at the start that scrutiny’s role is well articulated, and properly understood, amongst means that:

- Clarity on scrutiny’s role will ensure that scrutiny can deliver the greatest possible value, and will contribute reliably to the fostering and development of good working relationships;

- It will be easier for sovereign councils, later in the process, to come together to collaborate – including with the shadow authority. We set out possible arrangements for this below.

Scrutiny’s role at each of the five steps towards LGR

At each stage there is a role for scrutiny to perform at the sovereign councils and the shadow authorities – relating to the ongoing delivery of “business as usual” services, ending the work of the sovereign authorities well, managing the transition of those services into the new councils, and thinking about the aggregation and disaggregation of services in the longer term – leading in due course to wider transformation and savings.

The year of operation of the shadow authority itself will be a period of sustained, high pace activity. During this period the scrutiny arrangements, and activities, of the sovereign councils will need to continue. Existing councils will retain their duties and responsibilities. Decision-making (including long-term decision-making) will continue, and sovereign councils will continue to hold the same duties as they do now to act in the long term interest of the area and of local taxpayers – Government has been explicit that finances must be used with this in mind and it is a factor of the LGR process that scrutiny will need to have in mind as it carries out its work in councils’ final years.

The presence of the shadow will add complexity to the landscape, and to long-term decision making. This will demand a deft approach to co-ordination by scrutineers – especially bearing in mind the likelihood that resources will be very constrained.

1. Finalising proposals and waiting for Government’s decision

What happens during this stage

At the time of publication (August 2025) this is the place that most places are in. In some areas, final proposals will not be submitted until later in the summer. Some areas (specifically, Surrey) are being fast-tracked, have already submitted those proposals and await a Government decision sooner.

Councils will be:

- Finalising their submissions to Government;

- Putting in place the arrangements to ensure that they have capacity for the rest of the process – appointing programme directors for LGR, for example;

- Sketching out the overall timeline for the remainder of the process. Detailed project planning will be difficult at this stage;

- Starting to think about what “safe and legal” transition looks like – getting together a list of those services that need to be transferred to new authorities and beginning to explore the basic requirements of this transfer.

During this period there will not be much specific LGR related activity to scrutinise. Within individual councils, thinking and planning will be happening – but much of it general in nature.

What scrutiny might do

Scrutiny functions can productively use this time to:

Understand its position, its aims, its assumptions – to develop a baseline understanding of the picture (and where necessary to inform scrutiny’s thinking on where further work might be needed to flesh plans and objectives out in advance of the establishment of the shadow);

Time spent planning and reflecting pays dividends – not least because the remainder of the process will be fast-paced, and time and capacity will be tight.

Tension and disagreement is an almost inevitable part of the early part of the LGR process and, if it continues, there is a real risk that it can affect the capacity of sovereign authorities to make and deploy the plans they need in order for LGR to be a success;

The presence of disagreement may make this difficult or impossible but some form of early informal conversation – even if only at officer level – should be attempted. Conversations can be focused on the task for scrutiny to do on LGR, but also on sharing experiences about “business as usual” in order to get a clearer sense of members’ expectations across the area, and a sense about what the post-vesting scrutiny function for the new authority might need to look like, with its practices built on the arrangements of the current sovereign councils.

2. The structural change order

What happens during this stage

Once Government has decided on its approach to reorganisation it will prepare to lay in Parliament a “structural change order”. The SCO is the legal instrument that creates the shadow authority – it also puts in place the process by which that authority will assume responsibility for the delivery of services the following years. The SCO will usually be laid in Parliament, and come into effect, on the same day.

Those in leadership positions – leaders, chief executives and others – will be:

- Engaging with Government on the content of the SCO – on the name of the new councils, the total number of members they will have and other aspects of the formal constitution of new councils;

- Possibly, challenging Government’s preferred option. During this process one or more councils in an area may choose to judicially review Government’s decision;

- Finalising preparation arrangements – including assigning lead officers to take forward certain LGR workstreams and beginning to design joint project management arrangements, including bringing together leaders and other senior members to talk about the next steps.

The period between Government announcing its intention, and the laying and approval of the SCO, may only be a few weeks. The SCO itself is laid, and becomes law, on the same day. This will usually be in the January before the shadow authority comes into existence.

What scrutiny might do

During this comparatively short period, scrutiny can:

Confirming agreements with the executive and others;

To explore, and align, how the process might be managed across the sovereign authorities in advance of the shadow being established.

3. Joint committees and establishing the shadow

What happens during this stage

Once the SCO has been laid, joint committees will need to be established to cover the new authority areas. The establishment of joint committees are a legal requirement.

The leaders of the councils whose areas will be covered by a new council will sit on the relevant joint committee. Practically, this means that where Government plans to establish two or more councils in a two-tier area, the Leader of the county council will sit on more than one of these committees.

Councils will:

- Convene two or three meetings of the relevant joint committees to make recommendations to the shadow authorities on their initial setup arrangements, including their constitutional arrangements;

- Confirm programme arrangements for ensuring that the shadow has the officer support in place that it needs to manage its duties, and transition arrangements, from the start. This will involve some officers doubling up in their duties – working for shadows as well as sovereign authorities. In due course, permanent appointments will begin to be made to senior roles.

What scrutiny might do

Joint committees will set the framework for the tasks taken forward by shadow authorities. It is not likely to be necessary to establish Joint Overview and Scrutiny Committees (JOSCs) to mirror the joint committees, given that the joint committees will only be in existence for a relatively short period. Instead, the time can be taken to look at workstream plans / blueprints for transition and new service areas with a view to beginning to explore emerging strategic risks.

4. Scrutiny during the shadow year: in the sovereign councils and in the shadow

When the shadow is established there is a significant amount of tasks that need to be performed.

- Building capacity. The shadow will need to staff itself, and to ensure its workforce arrangements are in place to take on its duties come vesting day;

- Preparation for aggregation and disaggregation. This is the process whereby services are reorganised to match the boundaries of the new authorities;

- Safe and legal transition. This is the process by which the sovereign authorities ensure that they are passing the duties, assets and liabilities to the new councils in a seamless, managed way.

In carrying out this work the shadow and the sovereign authorities will need to have regard to their duty to co-operate, including the specific duties set out in any section 24 direction (see below).

Building capacity

When established, a shadow authority will have no assets – just its members, a constitution and the bare bones of a governance structure including a Leader and Cabinet. One of the first non-executive bodies to be established will be the scrutiny committee.

The shadow authority’s first AGM will be the point at which the task of “filling out” the shadow authority will begin. At first, workstream lead officers (who may originally have been chosen by the joint committees) will continue to exercise leadership roles, but in time the shadow will begin making its own appointments. Interim statutory officers will be the first to be appointed; the shadow will, through the year, slowly begin to fill out its senior management structure and to appoint people to corporate roles – in policy, communications, democratic services and so on. This process will begin in earnest towards the back end of 2026 – but during this period there are likely to be a large number of twin-hatting officers, continuing substantive duties at the sovereign councils while they step up operations at the shadow. Transfer arrangements, in the event that wholly new authorities are being established, are made through TUPE. In the event that, in some areas, an existing county council may have its legal status amended to become a unitary, different arrangements may apply.

Recruitment will most likely take the usual approach for redundancy exercises, where certain officers will be entitled to apply for certain roles depending on their substantive positions.

The bulk of public-facing staff will be transferred over to the new council, as their new employer, on vesting day.

You can read more about staffing issues relating to LGR in this LGA: Local Government Reorganisation: workforce issues

And in this article by Sarah Lamont from Bevan Brittan published by Local Government Lawyer: Understanding the key staffing issues in Local Government Reorganisation

Preparation for aggregation and disaggregation

Services operated by counties, and districts, need to be reorganised around new boundaries. This process involves:

- Aggregation – where district-level services need to be merged to cover the geography of a new unitary authority. For example, waste management services will need to be merged across former district areas to allow a new unitary to deliver a single unified service;

- Disaggregation – where county-wide services need to be split to cover the geography of more than one new unitary. Principally, highways management, adult social care and children’s services will need to be disaggregated. In certain circumstances some services can be preserved as county-wide, where a trust or other vehicle is established to deliver a service on behalf of the new councils.

In relation to social care councils need to satisfy themselves of the safety of the proposed approach – this is an important assurance responsibility which will need to be visible to members, including scrutiny members, of the sovereign councils as well as those of the shadow. The LGA offers support in respect of securing effective management arrangements for these changes – Test of assurance offer – to review senior management structures

The formal process of aggregation and disaggregation will not start until a new shadow authority vests. However, shadows are likely to have well-developed aggregation and disaggregation plans in advance of vesting, that shadow scrutiny is likely to want to understand and interrogate. In Cumbria the shadow councils developed a series of “blueprints” to define the post-vesting transformation.

Safe and legal transition

Managing the transition is a job for the sovereign authorities and the shadow, working together.

Legal obligations

An important part of the “safe and legal” transition is ensuring that the council’s legal obligations are understood, and that those obligations are clearly articulated to the shadow.

There is a significant job of work to do in handling and managing the legal aspects of transition – the transfer of contracts, for example, as well as setting the framework for the temporary “hosting” of services by councils during the process of aggregation and disaggregation.

Many of these issues will be similar area to area, but there may be distinct legal issues that apply uniquely to specific areas – local Acts where obligations need to be understood and where necessary transferred to a new authority. Formal arrangements also need to be made for the preservation of ceremonial civic rights where there is a place in the area (a city or borough) with a Royal Charter. Here, a new council will need to establish charter trustees. Failure to do so will result in formal status being lost – as happened in Rochester in 1998, where a failure to appoint charter trustees led to the town losing its city status.

Assets and liabilities

Sovereign councils will hold both assets and liabilities. Physical assets – buildings, for example, but also equipment – will need to be transferred on vesting day into the ownership of new authorities. Council reserves will also need to be, where necessary, divided amongst the new authorities and aggregated to a single new council. Liabilities will need to be managed similarly. Some councils may have large debts that will need to be serviced.

Section 24 Direction

Once the shadow has been established, Government will issue a Direction under section 24 of the Local Government and Public Involvement in Health Act 2007 requiring that the sovereign councils secure the consent of the shadow authority / ies for certain financial activities. This reflects the fact that assets and liabilities will be transferred to the new councils subsequently.

Example Direction

“The Secretary of State directs [the named sovereign authorities], being authorities which are to be dissolved by virtue of an order made under section 7 of the 2007 Act, that it may not, without the written consent of [the shadow authority or authorities, as relevant] : –

Example A

“Enter into any capital contract under which the consideration payable to the relevant authorities exceeds £1,000,000, or

Which includes a term allowing the consideration payable by the relevant authority to be varied…”

Example B

“…enter into any non-capital contract under which the consideration payable by the relevant authority exceeds £100,000, where the period of the contract extends beyond [vesting day] or under the terms of the contract, that period may be extended beyond [vesting day].”

What scrutiny might do

Over the course of the year scrutiny in the sovereign authorities can undertake some of the tasks that we set out in summary at the start of this guide:

This will include getting a sense of the council’s approach to risk management overall, consideration of the council’s appetite to risk and how mitigations are being managed. It also includes considering risks that may be escalated because they are complex, and difficult to mitigate. This is likely to include the consideration of risk issues arising from the transfer to the new councils of assets and liabilities (including reserves and debts). Some of this activity will be managed by the council’s Audit Committee. We have produced further information on the scrutiny of risk and risk management on Audit, Scrutiny and Risk

Particularly in the back half of the year, scrutiny can draw together insight and intelligence about the local area to pass on to the new councils that gives life and humanity to the drier forms of data that may be shared by other means.

While conventional scrutiny often has a long horizon, reviews plans for long term policy development, the limited horizon for the sovereign councils in the shadow year means that this long term policy development work will shift to the shadow – BAU scrutiny will need to become more focused on ongoing management and improvement of services, likely seen through the lens of the potential risks around ongoing delivery of those services;

Relationship management, equity and equality, ensuring that the process is visible to others (including local people) – scrutiny’s role can see it bringing into the public domain evidence about the management and transaction of the process, using this to test the resilience of the approach that councils have established to manage the change.

Shadow council scrutiny

In the shadow councils, scrutiny is one of the first member functions to be established.

Scrutiny’s functions here will necessarily be limited by the fact that these councils will, as yet, have no delivery responsibility.

What shadow scrutiny can do

This mirrors the scrutiny process as managed by the sovereign authorities and will require a degree of co-ordination. For the shadow, especially in areas where two or more new authorities will be created, one element of risk that scrutiny may wish to consider is the approach to hosting services prior to eventual disaggregation;

The shadow is unlikely to start thinking about post-vesting strategy and transformation until later in the year when corporate systems have been built up but the overall shape of this agenda may be identifiable through the plans for transition / transfer of services;

This is a once in a generation opportunity to build a brand new institution from the ground up. Members have an opportunity to support those in leadership positions to define how they want this institution to work;

Robust scrutiny arrangements will need to be in place for when the new council vests. These will need to be carefully designed – by scrutiny members, but involving a range of other stakeholders too, and reflective of wider good practice. There is an opportunity here for real innovation.

Whatever scrutiny does during this year will need to be balanced between LGR-related activity and “business as usual” scrutiny. As the year goes on, “business as usual” scrutiny will essentially merge with the business of designing the safe and legal transition, as the operating horizon of the sovereign authorities comes closer and closer to the present.

5. Vesting and what happens after

At the very end of 31 March 2027 existing county, district, borough and city councils in many areas will cease to exist; at midnight on 1 April 2027 new unitaries, previously shadows, will assume the legal responsibilities of those bodies.

On 1 April the same services, delivered by the same staff, will be being delivered to local people. In terms of service quality the transition should be imperceptible. But over time local people – and councillors – will start to see differences.

This is because vesting day will mark the start of an intensive period of transformation for the new councils. Aggregation and disaggregation will now happen at pace – transformational activity to redesign services around the boundaries of the new authorities, including renegotiating and redrawing contracts, are all part of this process.

This transformation is likely to take a significant amount of time and resource. It is likely that final arrangements to fully aggregate and disaggregate services will not be complete until 5 years after vesting day.

What happens beyond the horizon of vesting day is down to the successor authorities and, hence, something that is difficult to write about before those bodies come into existence.

LGR timeline recap

See this outline of LGR timescales from the Local Government information Unit (LGiU):

All resources

All resources