Governance risk and resilience framework: material for those with a leadership responsibility on good governance

The full governance risk and resilience framework is available on a separate page here. We have also divided additional material into two parts depending on your role within the council.

- Material for councillors and officers in general – those who do not have day-to-day responsibility for leadership on governance issues;

- Material for those with a leadership responsibility on good governance – in the first instance, this will be the principal statutory officers – the Head of Paid Service, the Monitoring Officer and the section 151 officer.

Material for those with a leadership responsibility on good governance

This part of the material is intended for senior individuals in local government to play their part in understanding, and acting on, risks to good governance – this page is intended to complement the content set out in the full framework on this page.

It is designed to align with the CIPFA/SOLACE, “Delivering Good Governance in Local Government: Framework” (2016). In particular, it engages with the sections of that Framework which relate to the preparation of a council’s Annual Governance Framework. Before reading the remainder of our framework we recommend familiarisation with the CIPFA/SOLACE framework.

A key function of our framework is about the way it gives access to a strong evidence base for the drafting of the Annual Governance Statement. This anchors the framework in a member-led, statutory process – an important part of highlighting its importance and conferring legitimacy.

It is particularly designed to speak to the individual and collective roles of the three principal statutory officers in the council:

- The Chief Executive, as Head of Paid Service;

- The Monitoring Officer, who may also be the Head of Legal;

- The Chief Finance Officer, who may also be referred to as the Head of Finance or the “s151 officer”.

This group are sometimes collectively known as the “golden triangle”, although in our material we will refer to them as the principal statutory officers.

There are also significant leadership responsibilities held by other senior officers, by certain councillors who, by virtue of their positions, also have an important role to play in ownership of these issues.

The framework

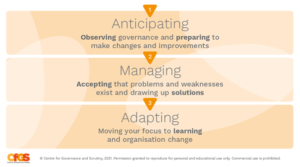

The framework consists of three stages – anticipation, managing and adaption. You can see the outline of these stages in our full framework.

Stage 1: Anticipation involves observation of, and preparation for, the emergence of governance risks. This involves you drawing insight and intelligence from around the organisation – which we cover in more detail where we talk about escalation, below.

The framework provides mechanisms to identify, tease out and discuss issues – in particular, the use of a set of seven characteristics to provide a common language for discussion on governance risks.

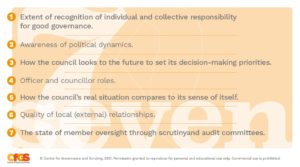

The seven characteristics

This set of seven characteristics has a range of positive and negative behaviours associated with it. You can find these behaviours here; they are arguably the most important part of the framework and reading and reflecting on them is what will help you to make a meaningful judgement on governance risk. You can also find the behaviours listed in a separate document which you can download.

- Extent of recognition of individual and collective responsibility for good governance. This is about ownership of governance and its associated systems;

- Awareness of political dynamics. This is about the understanding of the unique role that politics plays in local governance and local government. Positive behaviour here recognises the need for the tension and “grit” in the system that local politics brings, and its positive impact on making decision-making more robust;

- How the council looks to the future to set its decision-making priorities. This is about future planning, and insight into what the future might hold for the area, or for the council as an institution and includes the way the council thinks about risk;

- Officer and councillor roles. Particularly at the top level, this is about clear mutual roles in support of robust and effective decision-making and oversight. It also links to communication between key individuals, and circumstances where ownership means that everyone has a clear sense of where accountability and responsibility lie;

- How the council’s real situation compares to its sense of itself. This is about internal candour and reflection; the need to face up to unpleasant realities and to listen to dissenting voices. The idea of a council turning its back on things “not invented here” may be evidence of poor behaviours, but equally a focus on new initiatives and “innovation” as a way to distract attention, and to procrastinate, may also be present;

- Quality of local (external) relationships. This is about the council’s ability to integrate an understanding of partnership working and partnership needs in its governance arrangements, and about a similar integration of an understanding of the local community and its needs. It is about the extent to which power and information is shared and different perspectives brought into the decision-making, and oversight, process;

- The state of member oversight through scrutiny and audit committees. This is about scrutiny by councillors, and supervision and accountability overall.

You are likely to need to establish (light touch) systems to do this. The seven characteristics are designed to map to the “seven principles of good governance” in the CIPFA/SOLACE Good Governance Framework.

Stage 2: Managing involves taking the steps necessary to accept that the risk or risks exist, and finding solution. Accepting the presence of risk can be difficult in a political organisation, and it can present a challenge for people in senior leadership positions.

Stage 3: Adaption is about helping you to embed change and to learn from what has happened, to support continuous improvement.

Familiarising yourself with the framework will help you to be able to put steps in place to understand the two things on which you will need to take a lead, as a senior statutory officer, which are:

- The relationships which need to be in place to support effective governance. The relationship between the three principal statutory officers is particularly important, as is an understanding of their individual duties. But there are other stakeholders who have a critical role to play as well. Relationships between officers and politicians, – particularly leading members – are of vital importance

- The systems that councils can put in place to ensure those relationships work to tackle governance risk. These include systems to baseline your existing practice and activity on governance (including using the framework to reflect on governance yourself), and ensuring that systems exist to escalate governance concerns properly.

In an authority with an open culture, comprised of supportive and honest relationships between officers and members, it will be possible to have frank and candid conversations about governance risks and how they can be addressed. This guide explores how the principal statutory officers can assure themselves that they are leading and owning the development of such a culture, as part of a process of governance improvement.

The relationships necessary for the framework to operate

Taking action on governance risks involves looking at the places where leadership and ownership sits, and the relationships that need to exist between key groups. It covers:

- The organisation’s political leadership – and the impact of political dynamics;

- Senior officer leadership from the three principal statutory officers. Each of these officers has a unique and distinct role and set of duties. Collectively, they hold a leading responsibility for assuring good governance – but they aren’t the only people with duties here;

- The broader range of senior officers – some of these individuals will also hold statutory responsibilities, and understanding their duties in respect of governance (and the support they may need to provide to the three principal statutory officers) is important;

- The wider group of councillors and officers. Good relationships, bound with ethical conduct, will support the kind of candid and mutually supportive approach needed to identify and take action on governance challenges.

Relationships are not just about the council as an institution – [they are also about how good a council is at engaging others]. Councils have a huge number of partners, in the local area and beyond. All service design and service delivery has a partnership component. Many partners will have insights which will help the council to better understand its place in the local community, and to design its working arrangements accordingly.

“[Political challenge and debate] is entirely legitimate – although there will be certain behaviours that tip into being unacceptable, and councillors and officers will need to work together to understand where the boundaries lie.”

Local democracy is fundamental to good local governance. The role of councillors needs to be understood not only by those at the very top of the organisation, but also those in other member and officer positions. This is about ethical behaviour, adherence to standards of conduct as set out in places like the LGA Model Code of Conduct and the Seven Principles of Public Life, and a mutual understanding of where the member role rightly sits.

Strong political leadership brings accountability to local people and drives credible, legitimate decision-making which is focused on community needs. Party politics is also vital – it is the way that public debate can happen on competing political priorities. This may involve councillors attempting to block change and/or challenging it in robust terms. This is entirely legitimate – although there will be certain behaviours that tip into being unacceptable, and councillors and officers will need to work together to understand where the boundaries lie.

The kinds of issues flagged up through this framework should not be seen as evidence of a council on a slippery slope to failure. An approach to use of the framework which sees political risk in identifying shortcomings will be one which makes the implementation of solutions more difficult. Councils should in fact expect that use of the framework will identify matters of concern, and that through prompt action risks around those concerns can be mitigated.

In short, owning up to the presence of those challenges is a strength, not a weakness.

The principal statutory officers will want to have frank and candid conversations with political leaders about their likely response to these challenges as they arise. Governance arrangements are subject to ongoing review to ensure that changes in the nature of the organisation and its politics are recognised, and this part of the framework recognises this.

Where strong political leadership is absent, senior officers will need to recognise this and reflect on what it means for their role and responsibilities. This might be the opportunity to draw in external support – from the LGA, or other membership organisations.

Senior officer leadership from the three principal statutory officers

It’s no longer about: ‘I am the hero in my organisation’; it’s actually now: ‘I am a player in the system around the place’. And that’s an acute difference.

Deborah Cadman, Chief Executive, West Midlands Combined Authority, quoted in “Storytellers in chief” (SOLACE, 2020)

Modern leadership is about leading in a system, with the authority to convene and the humility to serve… Developing and making the most of relationships across our place. Doing things with people, not to people, and making the very best of dwindling resources. Spotting the flaws in systems we can’t change… and doing what we can as a local authority to alleviate some of the problems, to make things a bit better for our residents. Acting like a system, thinking like entrepreneurs. Gaining power and influence by giving power and influence away

Jo Miller, former SOLACE President, SOLACE Summit 2017

Like effective leadership, good governance is relational. It relies on a culture of strong individual responsibility allied to a collective responsibility held across the organisation. While the most senior officers (in particular, senior statutory officers) have particular responsibilities for the improvement of the organisation, good governance is a responsibility shared more broadly.

Ultimately, positive behaviours here should map closely to the Local Public Services Senior Managers Code of Ethics (SOLACE et al, 2017) and the Seven Principles of Public Life (“the Nolan principles”). These principles can usually be found in a council’s constitution.

Despite the need for clear ownership and responsibility across the council, leadership on action relating to corporate governance is a key duty of the three statutory officers identified above. This framework focuses on their specific duties in this activity – activity which is supportive of the wider member and officer corps in taking their own form of collective ownership.

Individual and collective responsibilities

Individual responsibilities held by the principal statutory officers

- The Head of Paid Service: designated under section 4 of the Local Government and Housing Act 1989, with the duty to report to elected members on the general organisation and administration of the council. Generally, the Head of Paid Service is the council’s Chief Executive;

- The Monitoring Officer: designated under section 5 of the 1989 Act, with the duty to report any breaches of the council’s, or the executive’s, legal obligations. The Monitoring Officer is usually a lawyer, although not always;

- The Chief Finance Officer: designated under s151 of the Local Government Act 1972 with responsibility for the authority’s finances. This person is required to be a qualified accountant under s113 of the Local Government Finance Act 1988.

Collective responsibilities held by the principal statutory officers

The individual responsibilities above will often intersect. Collectively, these three principal statutory officers have a responsibility to secure the authority’s good governance, because it is only through good governance that they can be assured of their ability to carry out their statutory duties.

The most successful use of our material will be from councils whose principal statutory officers individually and collectively possess the skills, respect and influence within the organisation to lead and effect change. Such officers will work together in a way that reflects an adherence to foundational ethical principles – in particular the “Seven Principles of Public Life”.

However, one marker of governance weakness – and risk – is where these relationships are not present. Our framework talks about this in more detail but examples may include:

- Where there is a perception that the loyalties of people in statutory positions are owed to the council’s administration, rather than to the council as a whole or the wider area. This is never black and white and some people’s perceptions of the situation will be different from others, which is why comparing subjective views on all issues is so important;

- Where senior officers’ roles might be stretched – because of a shared officer structure with another authority (although this does not automatically lead to weakness), because of director-level (or Chief Executive) vacancies, or any other ongoing activity which means that they have limited capacity at their disposal;

- Where some key statutory officers have a lower status than others. The risk of this with Heads of Legal has been well-reported. Occasionally, Heads of Legal and Monitoring Officers are more junior than section 151 officers, and a lack of seniority can bring with it a lack of presence at the top table, and a relegation of legal concerns. It is also possible for the s151 officer position to be marginalised, although given the specific duties of this role it is less likely;

In the section below we set out how the principal statutory officers can challenge themselves and their relationships, and understand and challenge some of the potential areas of weakness above.

Providing challenge and support

Senior leadership more generally

In order to effect proper governance, the principal statutory officers need the support of other officers, including other members of the leadership team. It is the responsibility of all the council’s leaders and managers to follow proper governance principles and ensure that they are embedded within the parts of the organisation they manage.

Councillors also need to play an active role. The Leader of the Council, Cabinet members, leaders of all political groups and the chairs of certain committees – for example, audit and scrutiny committees – will need to consider their own individual, and collective, responsibility and ownership of these issues. Councillors in prominent leadership positions have a particular responsibility to model good behaviours – this is something on which we expand when we talk about the seven characteristics which contribute to good governance.

Supporting the group of principal statutory officers

There are a range of other senior officers with important, and sometimes statutory, responsibilities – and officers who individually and collectively hold responsibility for statutory services. These may include:

- Corporate directors for children’s services and adult social care (as both strategic and operational decision-making ;

- Heads of internal audit (who have responsibility for delivering an annual opinion on the adequacy and effectiveness of the organisation’s framework of governance, risk management and control);

- Heads of governance and of democratic services, and the statutory scrutiny officer;

- Heads of communications;

- Heads of organisational development, transformation, commercial activity and others with a leadership responsibility in the council’s “corporate core”.

These senior officers may have a role in supporting a strong group of principal statutory officers – or in supporting the roles of those officers when relationships or capability may be weak. These form a halo or outer group, around the core group of principal statutory officers, who have a stake in leadership and ownership on matters of governance.

There will be others beyond the council, with insights and perspectives, and ideas, which might help those within the organisation to understand where improvements could lie. These individuals may not be the obvious people, such as senior professionals in other statutory services. Local people active in community support, for example, may be able to help the council to better understand the needs of the communities it serves and how its decision-making arrangements may need to change.

Officers and members overall

A good governance framework is designed to allow individuals and groups within the organisation to understand the issues and take action.

The framework can be used independently without the need for corporate activity tying it together – although the presence of such activity and leadership is of course ideal. If this is the case, those focusing on the issue might find it is the time to explore whether help from external bodies might be needed.

In the section below we set out how the framework can be used from the bottom up to develop an understanding of governance risk within particular parts of a council or across particular specialisms, and how this can help to develop a common understanding of the challenge the authority faces.

The systems councils can put in place

Any councillor or officer can use the framework to explore, discuss and understand the risks to governance of which they have experience, and it will provide them with the ability to use the professional skills to find solutions to some of those problems.

Everyone needs to know what will happen when a challenge emerges – how the problem is described, who takes ownership, who has oversight and so on. This is the system we describe as escalation.

This is not a place for complex systems. Officers and members will however need to have a clear sense of where their individual and collective responsibilities lie.

- Members and officers generally: using the framework individually and in small groups, possibly as part of management appraisal and team performance monitoring, or aligned to the authority’s values framework (where this exists). [We have produced separate material for officers and members on this point]. Here, the framework provides a form for conversations that are likely to be happening anyway. Officers and members, through this process, may identify smaller blockages and challenges which they can work individually and collectively to overcome. Some issues may be more significant, and may need to be escalated to more senior managers (and/or discussed candidly and constructively by politicians). The outcomes of this work can be shared with the wider organisation to assist in learning;

- Senior officers generally: gathering insights from their departments and that relate to how their responsibilities link to the council’s wider relationships in the community. Drawing insights together may identify cross-cutting issues which demand further investigation and action – senior officers can take these individually, or collectively with others in the organisation. Or on the most complex issues, the principal statutory officers may, individually and collectively, be called on to assist. Senior officers can also take the opportunity to look out into the community and into the council’s partnerships to understand how those relationships impact the resilience of governance arrangements. Weakness in partnership governance is likely to be something on which councils will need to take action too;

- The principal statutory officers: these officers, given the roles we have earlier described, have two particular jobs to perform:

- Satisfying themselves as to the health of the governance framework at large. These officers will need to know that other members and officers are dealing with governance challenges as they occur, that insights on these challenges are fed through to them, and that more complex issues are being escalated appropriately. This statutory duty – in particular the preparation of the Annual Governance Statement – is something that this framework is designed to support;

- Dealing with more complex issues: there will be issues which arise which may be more complex or difficult to deal with – matters which require a corporate response and/or the expertise of one or more of the principal statutory officers. The Monitoring Officer may have particular insights on governance challenges but the other two principal statutory officers will also have functions aligned to their statutory duties.

- Political leadership: members will have to bring oversight on the system as a whole – ultimately through debate and signoff of the Annual Governance Statement, but also through debate and discussion of complex governance issues at Council or in committee. A politically balanced Audit Committee that has responsibility for risk management and oversight of governance, can play a positive role and its members, particularly its chair, can act as governance champions. Members can also bring their own insights on where areas of governance strength and weakness lie. Members’ insights on these matters are likely to be especially useful as they will be framed in a different way to how officers might consider the problem, and the solutions.

The above systems are about providing structure and consistency to management processes which should already exist, not about putting in place wholly novel structures and processes. In the sections above we have laid out how others can step in to act if any of these systems lacks capability, or fails to act. In the section below on “anticipation” and “observation” we further explore the approaches to be employed here.

Some problems will be more challenging. Cross-cutting issues, and other complex issues, will need to be escalated. Escalation is one of the most important systems which will need to be put in place.

This where leadership from the principal statutory officers is most important. This is not about “monitoring” governance but empowering staff and councillors to take their own action to address behavioural issues, and being prepared to pick up the more complex problems. The focus on more complex issues – rather than firefighting on a wider range of matters – will help to inform both the Annual Governance Statement review process, and ongoing reflection on governance by senior officers and councillor.

This is all about thinking of ways to challenge and tackle “groupthink” – a significant risk in any organisation. Processes that encourage deliberation and invite scrutiny reduce these risks but don’t necessarily eliminate them.

Those in leadership positions have a responsibility for identifying this risk and acting on it. Having an accurate sense of where governance challenges and pressures lie in an organisation, and taking the steps to overcome those challenges, is easier where those in leadership positions have an overview of the whole system – a baseline, based on timely and accurate information. This relies on:

- Having the right relationships in place throughout the organisation to ensure that risks and issues can be brought to the attention of senior officers frankly and candidly, and that such actions are actively encouraged;

- Having the right mindset about “external” relationships, inviting comment and challenge from partners and others and using those insights to reflect and see where changes might be necessary. People from “outside” the organisation, looking in, may often be in a good position to identify issues which are less obvious to those “inside”.

The principal statutory officers have a leading responsibility here, but also a responsibility to support other senior officers (as well as officers across the council) and politicians to reflect on their own attitudes. Other senior officers have a responsibility to support each other on these issues too.

The principal statutory officers also have an obligation to reach out to others operating in the same area. Strengths and weaknesses in the governance of a council will have knock-on impacts on partners and partnerships. Local partners can play a vital role in assisting on improvement – the support, expertise and capacity of people from outside the organisation, but who understand the local context, could help to build and sustain resilience in many cases.

Without these positive, mutually reinforcing, relationships, it will be challenging for the principal statutory officers, and other officers and members, to get this accurate picture. People will be unwilling to come forward; there will be a tendency to only share good news. Problems may be resolved but only on an ad hoc basis, and the wider organisation may not learn anything from that resolution.

Ultimately it is about integrating “governance” into the day job, so that good governance is not something that officers and members need to consciously think about – it is just a seamless, natural part of their way of thinking and doing.

We suggest that the principal statutory officers will want to start by baselining their approach – testing the extent that a positive culture exists on governance in the authority. They can challenge themselves on this and invite challenge from others.

If you are one of the principal statutory officers, you will want to conduct an initial piece of “baselining” work which will involve looking at the framework in detail, and challenging yourself to answer:

- Are these components present in the way that we work now?

- How can I work with others to ensure that these components can be strengthened if they are weak or not present, or maintained if present?

You will certainly want to work through our framework yourself, and to reflect on your views of where governance risks arise.

Other senior officers may also want to carry out a similar baselining exercise – as may politicians with particular ownership or leadership responsibilities for governance. Different perspectives and judgements can then be combined to produce a more holistic view of the situation.

Some further questions to ask include:

- What am I doing, and what are we doing, to foster a culture where these things are taken seriously? Do we have an appropriate ethical framework in place?

- How do I know that I am successful in achieving these aims – what evidence do I have at my disposal to give me this assurance? What does this culture look like, in practice? (This is an issue that we explore when we talk about [escalation]).

- How am I proactively and visibly championing good governance?

- How am I supporting and promoting an approach to governance in the authority which is about a rigorous understanding of both individual and collective responsibility – and how am I ensuring that this understanding of roles is something which we bring, as an authority, to bear in working with other partners?

- What have staff and councillors’ responses to this work been? What does that tell me and other senior officers about what more we have to do?

- How am I working to support an environment where officers and councillors have the confidence and support to identify solutions to concerns and challenges, and to implement those solutions both individually and collectively?

- How do I know that I am getting frank and candid feedback from our partners on our interactions with other organisations – large and small – in the locality?

- How will I be able to translate all of this insight into findings that I can use to take defined, practical action to improve?

Aligning the framework with the Annual Governance Statement

Councils have existing systems in place for reviewing the strength of the governance framework – the Annual Governance Statement, which is a statement prepared by the council following a review of its governance framework, to provide assurance to councillors on governance matters (the AGS is required to be agreed by full Council). CIPFA has produced short guidance on the development of a robust AGS, which our framework complements. A 2020/21 version provides specific suggestions on the way that the AGS can connect to councils’ actions to support local people through the COVID-19 pandemic. More information can be found in the CIPFA/SOLACE “Delivering good governance in local government” framework (2016 edition).

This framework suggests that the AGS review process draw on insights derived from use of the framework across the organisation. The preparation of the AGS provides a “long stop” – a way for the council to demonstrate that it is taking these issues seriously. A superficial AGS which does not fully engage with the kinds of issues raised in this framework may present its own warning sign, on which members and officers might take action.