Introduction

What is the governance risk and resilience framework?

This material is designed to support individual council officers and councillors to play their part in identifying, understanding, and acting on, risks to good governance.

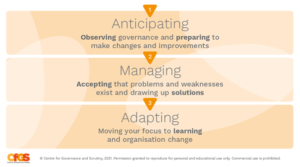

The basics of our framework is based on three stages –

- The seven characteristics which will help you to anticipate governance risk;

These are summarised below in our full framework, and you can also access the seven characteristics in full with the negative and positive behaviours associated on a separate page here, or download here - The ways that you can work with others to manage that risk;

- The ways that you can adapt your approach by learning from that experience.

|

Navigating our framework We have also divided additional material into two parts depending on your role within the council, both linked to separate pages below.

|

What do we mean by “governance”?

By “governance” we mean the systems and relationships which exist to support a council to be effective, well run and accountable. Good governance exists to ensure that councils achieve their intended sustainable economic, societal and environmental outcomes while acting in the public interest at all times.

Governance can be as limited as compliance with rules, and the law. Or it can be as broad as to encompass a wide range of associated behaviours and attitudes. Governance also covers the way that the council works with its partners and partnerships, and the way it understands the markets and relationships that underpin competitive services that it commissions, and commercial activity in which it engages. Particularly importantly, it influences the way that the council engages with the public that it serves.

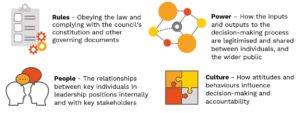

Core elements of governance include but are not limited to:

- Obeying the law and complying with what is set out in the council’s constitution and other governing documents. These are the basic rules and structures underpinning how decisions are made.

This involves making decisions which enhance public value, for example:- Clearly following agreed, well understood steps in the decision-making process;

- Transparently, through the facilitation of open debate, and through engagement and participation from those affected;

- In a timely, planned manner, with knowledge of available options and using judgement to make informed choices with accurate consideration of risks;

- With a view to monitoring and understanding outcomes, with results being reported and action to improve being taken as necessary;

- In an environment of trust and respect where roles are clearly understood.

- The relationships between key individuals in leadership positions (and other stakeholders in other positions).

- The relationships between those individuals and stakeholders and the wider public – how power is understood as a feature of decision-making, and how we seek to share it;

- How attitudes to all of the above influence and direct a council’s culture with respect to decision-making and accountability.

How can the framework be used?

The framework is not something that needs to be “adopted” by councils and does not operate as a checklist or process that can be used to evaluate governance risk. It provides a way for people within councils to talk about and reflect on governance, and to think about what steps need to be taken to act on emerging governance risks. In particular, it is designed to empower anyone in the organisation to identify and take action on such risks.

We envisage councillors and officers using the framework to talk about their experiences with governance, with these insights – and concerns – being escalated to principal statutory officers in a council for review. In some doing, this insight can help councils to agree robust and accurate Annual Governance Statements.

This framework is designed to reflect and supplement the CIPFA/SOLACE: “Delivering good governance in local government” framework (2016). It is also designed to engage with wider support provided by a range of national organisations and, in particular, with the sector-led improvement offer from the LGA. You can find out more about support offered by external organisations on governance risk here. We envisage that this material will be updated and refined in the coming months, based on the experiences of councils, councillors and officers who use it.

How was the framework developed?

This framework has been produced by a number of organisations in the local government sector to strengthen councils’ ability to make improvements to local governance arrangements.

It was produced by the Centre for Governance and Scrutiny and Localis over the course of 2019 and 2020.

You can read more about the development of the framework in our technical paper.

Download a PDF containing a summary of our full framework

The framework in full

Members and officers of the council in general may want to familiarise themselves with the framework in full to understand how their work – focused on anticipating governance risk – sits in context. They can also access additional material depending on their role within the council:

- Material for councillors and officers in general;

- Material for those with a leadership responsibility on good governance.

The principal statutory officers will need to look at the framework in detail to make sure that its components can function in their council. This is less about having formal processes in place and more about having the right behaviours and values. This process of baselining is something we discuss in another page intended for senior officer leadership. You shouldn’t expect that everything will be present – preparation for use of the framework is itself designed to highlight areas of lesser resilience, and where risk may exist at the very beginning.

Stage 1: Anticipation

This is about having strong systems in place to keep a “watching brief” on governance issues, and having the resilience to identify issues at the earliest stage. It is whereby insights from across the organisation are fed into senior officers and the principal statutory officers, to ensure that a whole system picture of governance risk and resilience can be built up. Ensuring that the system is in place for insights to be shared is the first thing to be done; if such a system is not present it will influence how other parts of the framework can be used.

Anticipation of risk is a responsibility shared by all in the organisation (we have written about it previously in the context of the particular role of scrutiny committees).

One of the main aims of this framework is to provide a “common language” to describe governance risks and behaviours that people can use to share their perceptions of what is going well, and what might be going not so well. The presence of this common language is one way that matters of contention – and political disagreement – around governance can be better discussed and understood. At the start, members and officers will need to think about, and talk about, how the framework can be integrated into how the council works so as to ensure that good governance is seen as part of the day job, not just an issue of compliance.

As insight and intelligence flows in, the principal statutory officers (supported by other senior officers and councillors with leadership responsibilities in governance) will need to consider how people’s subjective experiences and reflections can be triangulated

1a. Observation

This is about using the “seven characteristics” to keep the health of corporate governance under continual review through reflection on the characteristics and behaviours described above. It is about using effectively the system of reflection and review which we described in “anticipation” above.

We suggest that all officers and members can look to these characteristics to understand where they might hold responsibility, or oversight, on an issue where there are risks around resilience in governance. These characteristics are explained in such a way that makes them tangible to officers and members who might not think of governance as being “the day job”.

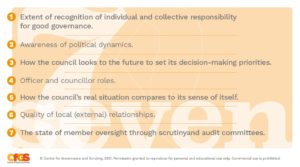

The seven characteristics

Each of our seven characteristics has a neutral description and is accompanied by a set of associated positive and negative behaviours, which will be used by the material as prompts rather than a checklist.

You can also access the negative and positive behaviours associated with these on a separate page here, or download here.

The headings invite you to consider the following points:

- Extent of recognition of individual and collective responsibility for good governance. This is about ownership of governance and its associated systems;

- Awareness of political dynamics. This is about the understanding of the unique role that politics plays in local governance and local government. Positive behaviour here recognises the need for the tension and “grit” in the system that local politics brings, and its positive impact on making decision-making more robust;

- How the council looks to the future to set its decision-making priorities. This is about future planning, and insight into what the future might hold for the area, or for the council as an institution and includes the way the council thinks about risk;

- Officer and councillor roles. Particularly at the top level, this is about clear mutual roles in support of robust and effective decision-making and oversight. It also links to communication between key individuals, and circumstances where ownership means that everyone has a clear sense of where accountability and responsibility lie;

- How the council’s real situation compares to its sense of itself. This is about internal candour and reflection; the need to face up to unpleasant realities and to listen to dissenting voices. The idea of a council turning its back on things “not invented here” may be evidence of poor behaviours, but equally a focus on new initiatives and “innovation” as a way to distract attention, and to procrastinate, may also be present;

- Quality of local (external) relationships. This is about the council’s ability to integrate an understanding of partnership working and partnership needs in its governance arrangements, and about a similar integration of an understanding of the local community and its needs. It is about the extent to which power and information is shared and different perspectives brought into the decision-making, and oversight, process;

- The state of member oversight through scrutiny and audit committees. This is about scrutiny by councillors, and supervision and accountability overall.

There is work that principal statutory officers, and others in senior leadership positions, can do to encourage and foster observation. This may link to a wider council programme on organisational culture change, or a values framework. Effective observation requires:

- A communicating culture based on openness and respect, not based on information cascading through rigid management hierarchies. The golden triangle can consider what such a culture looks like in a local context, and how they work to foster and develop it;

- An engaged and involved councillor corps, whose concerns and insights are taken seriously. The golden triangle can consider how they need to work with councillors, to understand the political dynamic within which they work and provide them with support in a tolerant and respectful environment. A robust attitude and approach towards the Code of Conduct and member and officer standards is likely to be a big part of this;

- A need to take external reports seriously – including auditor reports, reviews undertaken by the LGA, and external inspection by CQC/Ofsted. The principal statutory officers should take a particularly close look at engagement with external support. Such support is critical but its benefits can be occluded by defensiveness – sometimes from the councillor leadership, sometimes from senior officers. Particularly at the moment this kind of external support is critical – things like peer review are not fair-weather, “nice to do” activities, but fundamental tasks central to improvement and resilience at a critical time;

- A particular focus on financial monitoring, and the oversight, monitoring and ownership of risk (financial and otherwise). The s151 officer will be the person with the statutory responsibility to lead on this – others will have a duty to support this work. This person should already have a grasp on these issues but the question will be the extent to which these matters are understood and acted on by the wider authority. The s151 officer has an exceptionally challenging job – led by the s151, the wider cadre of senior officers can ensure that financial resilience is understood as a component of governance resilience more generally.

Elsewhere in this material we have suggested to officers and members a number of ways that they can seek to understand their own responses and reflections on governance, and how they can refine these insights by speaking to others.

For officers this would involve conversations:

- With others working in the same team or area (this might be a project team or a group of people who share the same line manager);

- Between the direct reports of a particular corporate director;

- Between officers with a shared professional specialism (for example, financial or legal professionals, or governance professionals).

For councillors this might be conversations:

- Between members of a single political Group;

- Between people on the same committee (a scrutiny committee, for example – scrutiny is likely to be a particularly useful source of insight on governance issues).

Under certain circumstances it might be appropriate for these conclusions to be tested by discussing them with people outside the organisation as well. Sector led improvement led by the LGA may be the way to achieve this while membership organisations such as SOLACE, CIPFA, LLG and ADSO may also provide mechanisms for this to happen. At a more local level, partners with whom councils work regularly could have their own insights. Later in this document we highlight the importance for the golden triangle in setting the tone on how external organisations are brought in to provide support.

1b. Preparation.

This is about having the mechanisms in place to respond quickly to concerns about risk and capability. The principal statutory officers will need to have the resources and capability in place to take swift and decisive action where and when concerns and problems occur.

In respect of the s151 officer and the Head of Paid Service, the need for appropriate resourcing to be in place is set out in statute. Even though a similar statutory prescription is not in place for the Monitoring Officer it does not mean that those duties are less important, and less requiring of resource. This includes:

- Establishing that the principal statutory officers, individually and collectively, have the capability and relationship to take action on these issues – and to exercise leadership and ownership. For various reasons this might not be the case. Other legal professionals, finance professionals, Heads of Governance and those with wider corporate and service responsibilities – of the kind we have discussed above – can come together to provide support to the principal statutory officers to ensure that corporate ownership of these issues does exist.

- Ensuring that the corporate capacity exists to respond to threats and risks, with clear political and organisational leadership from the top. The principal statutory officers can lead a process of scenario planning, thinking about how they will handle risks and threats. This is a planning process which should incorporate others and, as we detail on our page for senior officer leadership, this may form part of the formal review process preceding the agreement of the Annual Governance Statement.

- Ensuring that ownership of key corporate action and policies are understood so that action can be taken by the right people, at the right time, and in the right way – supported by certainty and rigour in the constitution and other governance documents. The golden triangle will consist of people who “own” the corporate plan on the officer side – a check to ensure that key projects, plans and deliverables are understood and owned is part of this responsibility;

- An awareness and ownership of good governance across the organisation, supported by regular training and practical conversations. The golden triangle can and should, as we point out elsewhere, play a prominent role in championing this sense of ownership. Plans for organisational development, improvement and transformation should prominently feature good governance as a behaviour, not just as a process.

- Having proper risk management systems in place, including mechanisms for governance concerns to be escalated (as discussed in the sections below). This framework itself hinges on risk. The principal statutory officers need to understand how governance risk links to wider corporate risk. Risk needs to be known, understood and acted on. Again, this is about behaviour, not just process;

- Looking to the examples of others in the sector to ensure resilience, including engaging candidly with national sector bodies. Principal statutory officers should look outwards, engaging with fellow legal and finance professionals and fellow sector leaders, to have candid and frank conversation with peers and membership bodies. As part of the development of this framework we have talked to membership bodies like SOLACE, CIPFA and LLG about how they can support the need for professional and personal resilience to their members on governance issues.

Stage 2: Managing

This is about ownership of weakness and being able to move quickly to identify a problem and then the solutions to resolve it.

Different risks will demand different mitigations and solutions.

2a. Acceptance.

This is the most challenging part of the framework. It is about the ability of individuals within the organisation, and the organisation corporately, to understand that a weakness exists. For leaders this is a particular challenge because it can be seen as an admission of personal weakness – the system which you own and for which you hold responsibility has been found wanting.

Some weaknesses may be systemic, and recognising them may involve asking tough questions of the organisation, its priorities and its values. There may be political and organisational risk in identifying such weaknesses if it is thought that they could cause reputational damage. On these matters, politicians will need to be informed and involved.

Action here requires:

- Acceptance of responsibility. For statutory officers, particularly for more serious weaknesses, this will be about fronting up, confirming that a weakness or concern may exist, and committing to taking action;

- Listening to those within the organisation (including councillors) voicing concerns and providing the space for those conversations to happen productively. For principal statutory officers, it will be critical to have clear lines of communication in place to ensure that where people do have concerns, they can express them candidly – and that the individual responsibilities of each of these officers is understood insofar as who is in the legal position to take action;

- Those in positions of responsibility (across the organisation) taking ownership of the issue and expressing a willingness and commitment to change. This is not just the duty of the principal statutory officers. Corporate directors, middle managers and – critically – the Leader and other key councillors will all have a role to play;

- An avoidance of overconfidence, and not underestimating the scale of the challenge. The principal statutory officers may be well placed to understand if an issue is perhaps a one-off, or if it is systemic, telling a more serious story about how things are done at the council. The way that the principal statutory officers work together will set the tone in how the organisation chooses to respond;

- Drawing together an awareness at the top of the organisation of issues critical to the business and subjecting them to particular scrutiny – a sense check of whether other weaknesses might exist as yet unrecognised. Where an issue or weakness emerges and is escalated to the principal statutory officers, proactive action may be required to stress test how the issue, and connected issues, are affecting governance in the organisation at large.

2b. Solutions

After an issue is surfaced, understood and acknowledged, this is about moving swiftly to develop plans for improvement. These may be informed and supported by people from outside the organisation, but would always require clear and unambiguous internal ownership. The nature and intensity of actions would be influenced by the seriousness of the risk. Action here requires:

- Solutions being brokered and agreed using a “one team” approach driven by a need for inclusivity. As a first step the principal statutory officers would need to set expectations that the development of solutions must be pluralistic. Different stakeholders will be able to bring different insights to bear which will inform and refine ideas for improvement. Just as acknowledging that weakness and risk exists is a public act, so too is the fact of drawing together solutions;

- Not focusing on a single governance “improvement plan”, but recognising that conversation and action addressing behaviours is more likely to effect change. Governance cannot easily be compartmentalised. Senior officers will need to ensure that solutions focus on values and behaviours as much as processes and systems. Importantly, actions will need to focus on clear, specific individual and collective accountability for specific change, which focuses on behavioural change rather than structural or process change;

- Actively seeking and using external advice but in a measured and proportionate way; not deferring to that advice but using it to construct solutions relevant to local circumstances.

- Putting in place plans for improvement which are actively acknowledged in the organisation as realistic. Senior officers have a task in brokering agreement – a challenge in a political environment, and why external support may be required;

- Effective external and internal communication to accompany the above. For an organisation going through challenges of this nature, “showing your working” by opening up about the challenge and the solution is likely to be uniquely challenging, but this openness and frankness is itself part of the process of governance improvement. Effective, strategic comms, led by expectations set by the golden triangle, will be central;

- Making a conscious break from past ways of working while still taking responsibility for them, and not forgetting the lessons. The golden triangle can help to set a new direction for the organisation, where the challenge or weakness is sufficiently serious to justify such a shift.

Stage 3: Adapting

This is about medium and long term change; a sustainable pace of change and making sure that those changes are resilient, and that they persist through the modelling of positive behaviours.

3a. Learning

This is about using the experience of solutions planning to inform longer term change – recognising that improvement is not just agreeing a set of short term actions to provide stabilisation, but is likely to involve more fundamental change.

Actions include:

- Continuing receptiveness to external advice, support and challenge;

- A restatement of the basic principles of leadership, responsibility and clear lines of accountability to ensure these issues are well understood – getting the basic building blocks right;

- Reflecting and learning on the need to focus and prioritise – as a key factor in good decision-making and in making further governance improvements;

- Reconnection with partners and the wider public – resetting and taking responsibility for rebuilding relationships, where necessary – building alliances and being prepared for others to take the lead.

3b. Organisational change

. This is about embedding short term solutions and medium term learning to ensure that a sustainable “watching brief” on risk can be established which can provide early warning of future risks.

Actions include:

- Investing in corporate capacity, including ongoing capacity to change (with the necessary resources to make this happen);

- Having a narrative about change and improvement, how it has happened and how it will continue, which is shared and collectively owned;

- Having the right people (with the right skills) in the right place to both deliver and sustain change and improvement;

- A renewed, and strong vision for the future which aligns decision-making and oversight activity to a corporate plan which confidently reflects local need;

- Having a clear and understood approach to risk appetite, which is followed consistently through the decision-making process and which is understood in how matters are overseen, escalated and delegated;

- Taking these lessons out to the wider partnership, and the wider area – using them to influence how the organisation might need to be redesigned so as to engage better with spaces and responsibilities beyond the “council” as an institution.

External relationships and organisations

A range of national bodies exist which can help you to explore and understand your authority’s governance challenges. National support is intended to complement work happening locally; our framework is designed to empower such activity.

However we do recognise that in some cases, councils may lack the culture and capacity to be able to adequately tackle governance issues. Worse, in some instances there may be a lack of corporate commitment or interest in doing so. In these instances individuals with concerns can find themselves isolated, particularly where they have concerns about issues which have not developed into serious wrongdoing, but which still seem serious.

We have suggested that councils should look out to their partners, to understand how partnership can help to bolster local resilience. Councils do not stand on their own – they sit as part of a complex web of local interrelationships. Authorities with strong governance understand these relationships and can work together with their partners – to support each other and to deliver common aims. The importance of strong local relationships is especially important as councils emerge from the pandemic and try to set the vision in a landscape dramatically transformed economically, socially, culturally and environmentally.

Councils with a more introspective attitude will not have these relationships. Partnership may be transacted on the council’s terms if at all. Reaching out at this stage, for support and advice, can be the first step towards improvement.

If however local conversations have not yielded any action you may find it useful to approach national membership bodies or other national bodies who have a specific role in providing support, usually confidentially, on such matters.

- The Local Government Association lead on improvement in the local government sector. One of the sets of behaviours we highlight is the engagement of councils with sector-led improvement and this particularly includes services provided by the LGA. The LGA offers in particular a regular “corporate peer challenge” to its member councils, and the framework provides a good way to prepare for and engage with this exercise. The LGA also offers specialist, subject-specific peer challenges. The LGA operates through a network of regional [Principal Advisers], who with regional programme managers work to support individual councils. PAs are likely to be a primary port of call for external support on governance issues. The LGA has several political group offices which can also provide support; Group offices can organise support from [councillor peers] who can provide direct support to councils.

- Membership bodies for the principal statutory officers, which will be in a position to provide advice and support to their members, including:

- The Chartered Institute for Public Finance and Accountancy is a qualification and membership body for public finance professionals. Most s151 officers, and other local government finance professionals, will be CIPFA members. CIPFA sets standards and provides detailed technical guidance on governance, audit and financial management issues, some of which is referenced in our material;

- Lawyers in Local Government is a membership body for local authority legal professionals. Most council Monitoring Officers will be lawyers (although not all);

- The Society of Local Authority Chief Executives, which is a membership organisation for senior officers (mainly chief executives) in the sector.

- Other membership bodies such as the Association of Democratic Services Officers, the membership body for governance professionals;

- The Centre for Governance and Scrutiny, the co-writers of this material, which is a body funded in part from the Government’s improvement services grant to provide advice and guidance to councils on governance issues. We provide a free helpdesk on matters relating to local authority governance and scrutiny.

|

We have also divided the material above into two parts depending on your role within the council, both linked to separate pages below.

You can access the negative and positive behaviours associated with the seven characteristics on a seperate page here, or download here. |

All news

All news